Standard 2

Contents

- 1 Text

- 1.1 The Five Foci of an Evergreen Education

- 1.2 Interdisciplinary Education

- 1.3 Personal Engagement

- 1.4 Linking Theory and Practice

- 1.5 Collaborative/Cooperative Work

- 1.6 Teaching and Learning Across Significant Differences

- 1.7 The Six Expectations of an Evergreen Graduate

- 1.8 Liberal Arts as Reflexive Thinking

- 1.9 Qualities of Evergreen Teaching Practices

- 1.10 Structural Elements of the Evergreen Curriculum

- 1.11 Undergraduate Curriculum

- 2 Standards

- 2.1 Standard 2.A - General Requirements

- 2.2 Standard 2.B - Educational Program Planning and Assessment

- 2.3 Standard 2.C - Undergraduate Program

- 2.4 Standard 2.D - Graduate Program

- 2.5 Standard 2.E - Graduate Faculty and Related Resources

- 2.6 Standard 2.F - Graduate Records and Academic Credit

- 2.7 Standard 2.G - Off-Campus and Other Special Programs Providing Academic Credit

- 2.8 Standard 2.H - Non-credit Programs and Courses

- 3 Supporting Documentation

Text

Evergreen is unique in American Higher Education, It identifies itself in the latest strategic plan as “the nation’s leading public interdisciplinary liberal arts college.” Its commitment to interdisciplinarity, to student responsibility, to collaboration, and its vision of an inclusive public egalitarian liberal arts education must be understood as the product of its history

The college must be seen as a response to the tensions around the critical debate within higher education in the nineteen sixties and seventies. This debate involves two quite distinct but crucial critiques that contributed profoundly to the college pedagogical and assumptions and practices. First was a critique of the multiversity. This was a critique of the large-scale public multi-disciplinary institution that had blossomed in the post-war years. From the point of view of this critique, most forcefully embodied in the Berkeley ‘Free Speech” Movement, the multiversity existed primarily for the benefit of a corporate/governmental interests. Its function was to maintain a supply of useful technicians and professionals. This critique saw the public university as serving class interests, of not living up to the ideals of a democratic educational system that would empower citizens broadly. The second critique was a critique of the liberal arts tradition itself as manifested in the small private liberal arts colleges. This critique began with the stodginess and irrelevance of the canon and the unwillingness of the college to take on the issues of race, class, war, and revolution. At the center of this critique was the failure the liberal arts college to act on its own professed values as it distanced itself the world of action. In the face of the crisis of civil rights, the Viet Nam war, and questions of class privilege the colleges were stuck defending texts, traditions, and positions that did not question the status quo. In the critique of the multiversity the question of moral judgment had no ethical basis, in the case of the small college the moral tradition and ethical questions were seen to be outdated, abstracted from the world, and hence irrelevant.

The founders of Evergreen, for the most part men and women in their thirties and early forties, wanted a college that was above all relevant and engaging. They wanted a public college that could provide the best elements of the liberal arts college – a college that could acknowledge and deal with ethical issues, one which saw the world as intellectually comprehensible and one which offered student opportunities to learn and act for the good of the community, not simply for individual or class aggrandizement. In short they were interested in public education as a public good. They wanted an education that would support action, engagement, and collaboration with diverse others. They wanted education within a meaningful community context. They wanted an education that was ethically informed. Simultaneously they wanted each student to take control of their own education, to make real value centered coherent choices about what they learned, how they learned, and what they did with the education they received. At the heart of this was a passionate debate about concern for authentic learning. All of the above characterizations of the college were contested, but in the crafting of the structure, the template the college has been tinkering with and transforming ever since, these were central values.

As was argued in the opening pages of this self-study the President and the founding faculty wanted to create a public college devoted to teaching and learning in a interdisciplinary, collaborative framework within which students must exercise autonomy and judgment. Charles McCann’s four nos: No academic departments, no faculty ranks, no academic requirements, and no grades were seen as a vehicle to liberate faculty and students. The lack of departments and ranks allowed faculty to work and collaborate across disciplinary boundaries and across differences in age and experience. The lack of requirements and grades freed students to work together to share and collectively create their learning. Collaboration, not competition, was seen as the fundamental vehicle for organizing teaching and learning. While within the college the breadth of the challenge to the conventions of higher education was reasonably well understood, the external world tended to know the college in its first decades on the basis of the above negatives.

The Five Foci of an Evergreen Education

By the mid 1980’s the need to rearticulate the challenge to frame the college around it’s positive vision for all the world (especially potential students and legislators) to see became an imperative. And in the work leading to the college’s first strategic plan and in the 1988 Self Study for Accreditation the five foci of an Evergreen Education were first enunciated. They have served the college well as a central embodiment of it’s mission over the years. The following section lays out the five foci and articulates the ways in which the foci implicate each other and lead toward the educational practices of the college.

The Five Foci of an Evergreen education, interdisciplinary study, personal engagement in learning, linking theory with practice, collaborative/cooperative work, and teaching across significant differences have played a central role in creating both a curriculum and a rationale for a curriculum. They inform both the programs and our articulation of them at all levels of the institution. These foci capture much, but not all of what we do at Evergreen. Many of our actual activities can be understood as contributing to more than one foci.

Interdisciplinary Education

Interdisciplinary study is a fundamental at Evergreen. At the heart of such study is the intellectual conviction that nothing can be fully know in isolation and that for us to know complexly demands that we see from diverse perspectives and ask our own questions of the phenomena we study. Interdisciplinarity is seen as providing students with at least three crucial intellectual understandings that help them recognize their perspectives and generate their questions. First, different disciplines can indeed hold different and valid understandings of the “truth” about some particular phenomena. Thus interdisciplinarity helps force students beyond a simple view of truth or falsehood and forces them to complicate and contextualize their view of truth. Second, Interdisciplinarity illustrates the ways in which different disciplines illuminate differing aspects of reality thus complicating student’s views of what a phenomena actually is. Finally an interdisciplinary understanding of the real world more accurately reflects the world as they do and will encounter it.

There is little orthodoxy about which church of interdisciplinarity we attend at Evergreen. It is important to note that all that is interdisciplinary is not team teaching and vice versa. Individual faculty members can expose students to more than one discipline and single program with two faculty members with similar back grounds may or may not be interdisciplinary. Acolytes of multi-disciplinarity, thematic study, project based experience and more teach at the college, yet nearly all agree that interdisciplinary work provides the essential pattern that allows for the emergence of connections, the creation of new kinds of understandings, and ultimately the possibility for students to find their own way/work into the curriculum.

Personal Engagement

Personal Engagement has multiple dimensions at Evergreen. At the heart of it is a desire that students develop a capacity to know, speak and act on the basis of their own self-conscious beliefs, understandings, and commitments. Thus critically the idea of one’s own work that emerges and develops throughout a student’s participation in the curriculum over time is central to their sense of engagement. The emphasis on participation, on reasoned evaluation and involvement in their own, their colleagues, and their faculty’s work strengthen this engagement. Such engagement is reflected in the college’s emphasis on full time work for 16 quarter hours per quarter. The lack of graduation requirements further pushes students to make reasoned choices about their work and presumably impels them toward creating a body of work that reflects growing intellectual sophistication. Such work could in the end be something quite conventional, a doctor, a wildlife biologist, a philosopher or it could be rather unconventional, a Kayak maker, an independent film-maker, or a specialty vegetable farmer. What would distinguish this work would be the way the work implicates the person as whole.

Finally, work in programs, especially programs that extend across several quarters, is engagement in a full time learning community. Here the relations are to the material, but also to the persons with whom they work. This conflation of persons and materials can lead to an intensification of engagement that creates powerful shared intellectual, social, personal, and aesthetic excitement. Students discover that personal engagement and engagement in a community are often complementary realities. This complex reality in which students are both pursuing their own goals and doing this through shared endeavor and cooperation is the center of the experience of a learning community and critical to most student’s experience of Evergreen.

Linking Theory and Practice

Linking theory with practice arises naturally from the engagement of students to their work in a social context and from the experience of interdisciplinarity. Both suggest that knowledge exists not simply for its own sake, as an isolated artifact, but as a part of some larger intellectual, cultural, or political whole. The necessity of linking theory with practice for the college arises out of a central concern for educational relevance and the college’s fundamental commitment to providing an education that will promote effective citizenship. Engaging in a conversation between theory and the experience of practice strengthens both and allows students to place their growing sense of personal work and commitment into a realistic and purposeful context. Theory, central concepts, or ideas then are constantly tested in three major ways in student’s experience at the college First and most significantly students are constantly asked to take their experience in the classroom into the world, in hands-on projects, internships, performances, presentations, case studies, and a wide variety of research work. Learning about a phenomenon is frequently tested against the experience of it. Ideally an Evergreen student should be learning and being challenged in both worlds. Beyond this theory and ideas are tested against the disciplinary and interdisciplinary phenomena it is purported to explain. Does the theory in fact illuminate the phenomena? If so how and to what extent? Finally, theories and ideas are tested against the context of culture and society within which they arise. How do theory and ideas inform cultural practices? How are theories and ideas explained by power relations, religious interpretation or some larger cultural/social reality? Thus the linkage of theory and practice is fundamental to the development of judgment, to the awareness of the cultural and political dimensions of knowledge, and the creation of active citizens who are capable of entering into dialogue with the world in which they live.

Collaborative/Cooperative Work

Collaborative/cooperative work is a cornerstone of the educational experience at Evergreen. The capacity for sharing and creating work within a cooperative context of respect for individuals and their diversity of perspectives, abilities, and experiences, is a central motif of nearly all Evergreen studies. In an array of practices such as seminars, group projects, narrative evaluations rather than grades, peer review of student work in all fields, the frequent inclusion of students from widely diverse and levels of back-ground and experience within programs, the fundamental assumption is that students can benefit from working with each other to create their education.

The fundamental pedagogic assumption is that collaboration is in the long run more conducive to the creation and acquisition of complex understandings and useful knowledge than is competition. By creating collaborative learning communities the college seeks to create both a context within which quite diverse ideas and concepts can be examined, but also a context that allows students to bring within the classroom some of that array of conversation and learning that in most schools occurs informally. This inclusiveness of experiences and ideas both from other portions of the program and from student lives creates the possibility that learning communities can capture and promote the experience of real dialogue about ideas, texts, art and experience that make education engaging and exciting. Finally, the college encourages cooperation because we believe despite the rhetoric of competition in this society most of the work that is accomplished is a product of cooperative engaged choices.

Teaching and Learning Across Significant Differences

Teaching Across Significant Differences reflects the fundamental recognition that we do not bring to our experience of education the same array of qualities and life experiences. These differences are both the source of our capacity to learn from each other and, potentially, a barrier to that learning. These differences are both socially defined and personally experienced. They include such obvious and important categories as race, ethnicity, religion, class and gender which underlie so much of American experience, but they also include less obvious and well defined and understood experiences as age, disability, first generation college experience, rural or urban up-bringing, or personal qualities such as sexuality, intelligence, shyness, mental illness and the like. Differences bring within the context of the college both a potential for great learning and a possibility of great damage. They call upon us to develop qualities of respect, attentive listening, and sensitive and thoughtful speaking. They are at the heart of our capacity to communicate and participate responsibly in a diverse community. Central to Evergreen’s experience of these differences is the practice of narrative evaluation and the desire to promote collaboration. While these practices have their own pitfalls, they suggest that a single standard and an assumed uniformity of experience is not the case and that respectful recognition and awareness of difference is an essential element in working with students to help them define and achieve the overall goals of an Evergreen education.

The Six Expectations of an Evergreen Graduate

In the 1999-2000 and 2000-2001 School years at the urging of the commission the college undertook a review of it’s understanding of General Education. During two years of debate, discussion, and struggle, the college produced an important document that attempted to articulate the goals of an Evergreen education from the point of view of the student. This document – The Six Goals of An Evergreen Education - has proved useful in articulating for advisers, students, and prospective students some of the elements that describe and effective pathway through Evergreen. The goals are understood to be just that – goals- not subject matter requirements nor mandatory skills. Thus students may, and often do, undertake meeting these goals, the requirement in fact falls on faculty to to make sure that as often as it makes sense the opportunities to meet the goals are present in the curriculum. As will be more explicitly argued below the goals main complex and important ways onto the five foci and can be seen as a rearticulation of the goals in terms of potential outcomes for students.

The Six Goals of an Evergreen Education are

- to articulate and assume responsibility for your own work,

- to participate collaboratively and responsibly in our diverse society,

- to communicate creatively and effectively,

- to demonstrate integrative, independent, critical thinking,

- to apply qualitative, quantitative and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines,

- and, as a culmination of your education, to demonstrate depth, breadth, and synthesis of learning and the ability to reflect on personal and social significance of learning.

The work students are capable of is seen as complex, linking and engaging analysis from different disciplinary perspectives, responsible in seeing a cultural/social context, communicable, and significant both to the individual and his/her society. Such an education then neither replicates the faculty, nor simply replicates the disciplines, traditions, professions, and skills that they profess. Instead, it encourages each student to ask his or her own questions, to test their own hypothesizes, and to make new mistakes. This education is at once potentially conservative and radical. Conservative in that one’s work is tested against the society and academic disciplines broadly, radical in that it is always implicitly a challenge to our conventions and knowledge. At the heart of Evergreen’s understanding of education is a belief that whatever that education is in terms of substance, it should be self consciously and reflectively chosen by the student. Central to the goals of the college is the capacity of each student to see and articulate their own work in the context of their engagement with others. Skills and capacities are seen not as simply autonomous and instrumental, but as embedded in the context of a person’s education as a whole and more broadly embedded in the social order through the participation in and reflection on that order by students.

The five foci and the six expectations are different articulations of very similar understandings about the central nature of Evergreen. The foci speak primarily to the content and nature of the curriculum offered. They articulate the emphasis on interdisciplinarity, cooperation, work across difference, the constant interplay of theory and practice, and student engagement. The six expectations are an expression of the qualities a curriculum organized around these ideas should be manifest in its graduates. Here is one version of the relationship of the foci and expectations.

Personal Engagement – Articulate and assume responsibility for your own work. Participate collaboratively and responsibly in our diverse society. Reflect on the personal and social significance of your learning.

Teaching and Learning Across Significant Difference – Participate collaboratively and effectively in our diverse society. Communicate clearly and effectively.

Collaboration - Participate collaboratively and effectively in our diverse society. Communicate clearly and effectively. Articulate and assume responsibility for your own work.

Linking Theory and Practice - Apply qualitative, quantitative, and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines. Demonstrate integrative, independent, critical thinking. Demonstrate depth, breadth, and synthesis of learning and the ability to reflect on the personal and social significance of that learning.

Interdisciplinary – Communicate creatively and effectively. Demonstrate integrative, independent and critical thinking. Apply qualitative, quantitative, and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines.

Liberal Arts as Reflexive Thinking

One way of expressing some critical aspects of Evergreen as an interdisciplinary Liberal Arts institution centers on the concept of reflexive thinking. This way of understanding the central work of the liberal arts – to promote reflexive thinking- helps us see not simply the contingent, but necessary ties among the five foci. It has the advantage of bringing to the fore the public nature of learning the complex mix of public and private knowing, and the centrality of freedom and responsibility that is contained in acts of judgment. By simply asking how can I know this? How does this affect me? Where did I come from? Students are pushed into a world that entails the holistic view of the world implicit in the work of a Public Interdisciplinary Liberal Arts college.

Reflexive thinking is not simply the act of the learner reflecting on what he or she has learned. Reflexivity is the capacity for that a learner has to think about the situation and conditions that underlie her own personal and collective experience of thinking. It implies that the learner needs to be aware of how she has learned and what she has become through the process of learning. This form of thinking makes the learner a problem for her self. Not only does she need to know the ostensible subject of the learning, but that subject matter is embedded in whole array of questions that ask questions about her own motives, embeddedness in society, desires and development. But beyond that reflexivity brings the learner to ask questions about how the ostensible subject of her learning has come into being in a society. How an approach to knowing (a discipline) and she as she becomes associated with the discipline become embedded in a complex historical and social web of connections that underlie that discipline. Beyond that the learner comes to see herself in the present as interacting with others through the learning she has entered in to. This form of thinking that makes problematic our understanding of self and society makes interdisciplinarity a necessary condition of clearly understanding ones position. It arises as a learner comes to see each discipline as a partial account of knowing himself in relation to the world and knowing. We are problems for ourselves that must be seen as arising from multiple points of view.

As learners come to understand themselves, both singular and plural, and learning in this complex way, they start to exercise judgment. The learner starts to exercise freedom to make judgments about what he has learned about himself, the material, social conditions that allow this way of knowing to exist. In other words the learner starts to exercise freedom and responsibility about the knowledge he has about the society and himself. By making these judgments and exercising this freedom the learner creates new meanings. These meanings typically do not take the given assumptions that lie behind the disciplines as settled truths; they inherently challenge established understandings. This process of creating new meanings, of creating new knowledge necessarily engages the learner with others in a public process of sharing understandings. Participating in this world of reflexivity pushes the individual learner to recognize difference and diversity of views and positions. In particular it demands that the learner engage not simply in reflection but in representational thinking, thinking through the eyes of others. This extraordinarily difficult and never completely successful mode of thinking, forces a learner to take seriously the understandings and ways of perceiving and knowing that exist in the world. This process of thinking though the eyes of others demands that the learner and indeed the community he/she is a part of must learn to think historically. This means that we see how the structure of ideas that define our views of others has come into being and is changed over time. It also implies that we see how the social institutions that have grown up historically to define the place of others and ourselves in a society. Thus reflective knowing is ultimately necessarily both very personal and political.

Qualities of Evergreen Teaching Practices

The foci link to the expectations through the student’s experience of the curriculum and the practices and assumptions on which it is built. Practices such as the assumption of full-time study as the preferred structure of student work or problem centered thematic programs, interdisciplinary work, seminars as central learning spaces, workshops and small group practice as regular elements of the curriculum and the like. But the most central practice, the one that has the most critical impact on student experience writ large is the experience of student autonomy.

At the center of the foci and expectations as two articulations of the college’s ambitions for its curriculum and its students is the individual student. The first of the expectations is to articulate and assume responsibility for your own work. Central among the foci is personal engagement with their educational experience. The student is understood in both these articulations as the central actor in their own education. The primacy of the student is most clearly and powerfully exemplified in the lack of degree requirement. 180 quarter credit hours of anything earns you a BA at TESC. On the one hand this is a terrifying recognition for faculty and administrators. Here in one simple action the whole apparatus of curriculum /requirements/majors/established disciplinary boundaries is relinquished into the hands of students. On the other hand this student autonomy is the foundation of those most prized qualities of student engagement, creative independent thinking, interdisciplinary work, work across difference. For the autonomy that students face forces them to ask their own questions. As they ask these questions and work with others to understand them, they are pushed toward deeper and more complex engagement and come to see the necessity for more complex interdisciplinary critical and creative thinking.

The end of program review data provides an extensive overview of the extraordinary array of teaching practices at the college. Four critical qualities emerge from this data. (A caveat not all programs possess all qualities, but all qualities can be found in all areas of the college.) First, teaching practices at the college are distinctly and exceptionally collaborative. At the root of this is the central notion that individual evaluation not competitive grading is the fundamental form of assessment. This root practice makes (reference to McCann No Grades, No Departments, ….) a huge difference in the classroom. Students are not penalized for sharing information and understandings and indeed the sharing of ideas and understandings is the central focus of that most Evergreen of institutions, the seminar. Collaboration is built into the structured workshops that are used to teach everything from writing and philosophy, to botany and mathematics. Small group research projects whose audience is the program as a whole are common. The idea that each person is responsible to the group to participate, to help build understandings, and to share what they know is fundamental to the life of programs as learning communities.

Second, teaching practices at TESC ask students to find ways to apply the understandings they have developed in class to the practice of that understanding both in the “real world” and in the experience of that work. (rephrase) Applications are built into field trips, into field study, into art making, into internships, into community service, into fiction writing, into laboratory research in the sciences, into the composition of music, into the creation of computer applications, qualitative and quantitative field research, into ethnographic research, into life history research, into film-making, into travel and cultural studies. The list goes on, but the point is that learning is not just talk about doing; it is an interaction of doing and talking, about learning, doing, and reflecting.

Inquiry based teaching practices are fundamental to much of what happens at Evergreen. At the level of the program nearly all programs have a set of central questions that they are taking as the central animating issues in the program. Here are a few from the 2007-8 Catalogue.

“What is the structure, composition, and function of a temperate rain forest? How does this relate to the ecology of other systems, land management and the physical environment? What do Chemists do? What is life exactly? What are the physical and chemical processes of life that distinguish it from ordinary matter? Are there mathematical rules that govern the formation and growth of life? This program is an inquiry into the numinous, which Rudolph Otto, amidst the turmoil of WWI, explained as a “non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self.” Have you wondered about the ways languages work? Do you think about how thoughts get translated into language?”

Within programs students are encouraged to chose questions to answer about the texts, often time they are urged to develop major questions as independent inquiry/research papers about issues developing around the program’s themes. Students are actively taught how to use library, computer resources, writing resources and experimentation among other skills as vehicles for answering questions that they pose, to find answers ( or further questions) that they have a stake in.

Finally, students exercise choice. Most importantly and obviously over the whole structure and content of their education, but at the level of the program and the work undertaken in any given quarter students exercise a wide range of choice . Internships, individual contracts , research projects, supplementary classes are all major opportunities for students to fashion components of their work around their choices. Even when students only select a program their capacity to see that program as a part of a larger choice driven project makes the act of taking it somewhat different from choosing to take another course towards a major in a conventional school.

These four elements then, collaboration, application, inquiry, and choice characterize the vast array of teaching practices that translate the language of the five foci into the experiences that produces students whose educations can be characterized by the expectations and the data we have reviewed. They provide the matrix of choices and opportunities that frame the dilemma of how to put together his/her work that each student must confront.

Structural Elements of the Evergreen Curriculum

The curriculum at Evergreen is designed by the faculty to further students’ ability to develop and meet the goals of an Evergreen education. The practices and structures implemented in the educational experience embody both complex substantive learning and the five foci. Four critical elements underlie the structure of the curriculum at Evergreen: team-taught coordinated study, full time study, student self-direction, and narrative evaluation. While none of these elements are universally present, they most clearly and distinctively embody the practices and goals of the Evergreen educational experience.

Coordinated Study Programs

Coordinated Study Programs are the distinctive mode of study at the college. A coordinated studies program consists of two to four (in the deep past as many as 7) faculty who together plan and deliver, generally full time, a course of study organized around a theme or body of knowledge to 50 to 100 students. Programs can be as short as one quarter or as long as three. These programs are often centered on a specific theme or set of questions that invite exploration from two or more disciplinary points of view, or they may be linked conceptually around method or subject matter in a way that promotes more complex understanding of disciplines by being taught in a collaborative fashion. In addition to coordinated study programs Evergreen offers single faculty programs provide full-time study of advanced topics.

By providing a structure which links ideas, questions, disciplinary understandings together with a specific on-going group of faculty and students, coordinated study lays the groundwork for the formation of an academic community. By having the full attention of students and extraordinary freedom to design programs, faculty members are empowered to create very different often innovative, usually exciting, learning experiences. Programs can, and often do, require, major field trips, built in research times, intensive laboratory work, opportunities for travel, productions, exhibitions, and a wide variety of smaller scale curricular innovations. Ideally faculty members help shape a multi-dimensional, multi-leveled conversation that helps students form and shape their own work and builds a knowledgeable audience for their writing and research. Within a coordinated study students and faculty can develop strong friendships, working relationships, and intense conversations that draw heavily on the shared experiences of the texts and activities of the program. Coordinated study as a concept has been usefully adapted to a wide variety of time frames, persons, and levels of work. Today it is found in some form or another in Graduate programs, off-campus programs, and throughout both the full and part-time undergraduate curriculum.

Coordinated studies, their part-time counterparts, and single faculty full-time Programs are organized into the curriculum of the Graduate Programs (MPA, MAT, and MES), the Tacoma Program, and the community based Reservation Program, as well as the undergraduate program on the Olympia Campus. On the Olympia campus the array of offerings is organized and coordinated through five planning units (Environmental Studies; Culture, Text and Language; Scientific Inquiry; Expressive Arts; and Society, Politics, Behavior and Change) and the Native American and World Indigenous Peoples Center. These areas will be discussed fully below.

Full-Time Study

Most student work at Evergreen is carried out in one form or another of full- time study. The pedagogical rationale here arises out of the coordinated study programs, especially those with a thematic base. These complex, multi-stranded, highly integrated programs make little or no sense when significant elements are removed. Similar intensive full-time work is often expected in single faculty full-time programs. This feature of the college both provides the intellectual intensity described above, but also provides the flexibility of scheduling that allows the college to offer genuinely innovative work in a number of fields where large blocks of time and travel are required. Beyond this the reality that most faculty, in most programs, have control of most of their students’ time in class , and meet with those students generally 14-20 hours per week means that they know their students needs, capacities, and desires well. This knowledge both allows for strong guidance and modification of program tasks, and allows complex reflective evaluations of students, and lays the ground work for effective advising. Full time study is obviously not a necessary feature of part-time work and the college has allowed significantly more part time work in recent years.

Student Self Directed Study

While the structure of the college’s program offerings provides a series of pathways that students may follow in pursuing their education, there are no requirements for graduation beyond the accumulation of 180 quarter hours credit. Many of the pathways will be described in the discussion of planning units below. This open invitation to students to design their own work at the college has been a central feature of student experience from the beginning of the college. It is based on the assumption that by working with multiple faculty and being exposed to a variety of disciplines, questions, and practices each student will begin to develop a clear pattern of interests and can, with faculty and advising help, find a way to build an educational path that has is exciting, demanding, and persuasive for each individual student. Choices are not entirely unconstrained, prerequisites, finding and appropriate faculty member for an independent study or internship may limit a student’s choices, but underlying all this is the faith that students can in fact identify and pursue their own work. Clearly the decision of the college to put students in charge of the choices they make to create their education is a radical one. Indeed of all the founding “Nos” the most radical in many ways is the relinquishment of the faculty’s authority to determine for students what it is that is important for the student to study. To the extent students take this challenge seriously they create an education that necessarily implicates them selves as person, not simply as products of an educational system or consumers of educational prescriptions. Individual contracts and internships are one important manifestation of student autonomy.

Narrative Evaluation

Evergreen’s origins as a innovative “experimental” college, the rejection of tenure and the substitution of three year renewable contracts, and a flat administrative structure imbued the college with a “culture of evaluation” at the institutional level, while the decision to reject standardized grading provided an impetus for careful work on evaluation of student achievement by both faculty and students. Narrative evaluation of student work is premised on the assumption that to create a community in which cooperation is central, evaluation must be personal, not invidious. A narrative evaluation is based on the idea that attempting to place each student on one scale when each student is pursuing the work of the program for different ends with different backgrounds and capacities makes little sense.

Evaluation takes many forms at Evergreen, but at the heart of the educational process is the faculty evaluation of students. This document reflects the faculty’s authority to grant and withhold credit, to identify the transferable content of the work, and, more importantly, attempts to identify the strengths and capabilities of the student and to locate his or her most important work within the context of the program’s themes, content and experience. Student narratives offer a critical response to the educational experience and often provide the rationale that links one educational experience to the next. The capacity for students to provide their accounts in the transcript evaluation speaks to the college’s commitment to taking students and their account of their experience seriously.

Formal evaluations, the ones that appear in the transcripts, are important, but their significance is primarily documentary and retrospective. Informal evaluations, the ones that occur within programs have the quality of being retrospective and reflective on the one hand and prospective on the other. They situate the student and the experience in midstream and ask for an assessment, adjustment, and reframing. Student self-evaluations review and their work and introduce their in-program portfolio. Faculty in conferences asks the student to connect his experience in the program with his work, to think about how he can come to own this experience as his own education, and provides an assessment from the faculty member’s perspective. This process of reflecting is not only on the direct content of the program, but often on the experience of learning. Students are asked how they have changed as learners, how such basic acts as reading, knowing, writing have changed for them through experience. This evaluation practice, seeing ones learning and competency develop, opens up questions and helps students see the path both within the program and in the end of the term it may, and often does provide a key to where to go from here.

The evaluation process is both formal and informal. Informal evaluations by both faculty and students are written documents focusing on the students learning, opportunities for improvement, and possible future directions. They are written by both faculty and students and are discussed with students as a part of a review of student’s work at an evaluation conference at the end of each quarter. The preparation for this review by both students and faculty is a major opportunity to reflect on future directions and to develop a reflective critical assessment of the work of the student and the program.

Three major initiatives in the past 10 years have affected transcript evaluations. All of these start from the premise that a complete and well written transcript is an asset to students as they proceed from Evergreen and a resistance to the idea of reducing evaluation to grades or rating forms. They reflect the need to create more concise and well-voiced evaluations in a timely and coherent manner. Two DTFs the first in 1997-98 and the second in --------- produced a set of arguments for the continuing utility of the evaluation process and support for the idea that there was not one universal process for evaluation. The latter DTF developed an important document on faculty narrative strategies and provided guidelines on the length and nature of the evaluation process. A second DTF in ------------- focused on procedures for the reorganization of the handling of evaluations and their storage and maintenance as electronic documents. This process has speeded the production of transcript evaluations. The formal faculty evaluation documents contain a program description identifying the work of the program, a formal assessment of the student’s work, and the identification of the program’s activities as equivalencies.

Undergraduate Curriculum

The undergraduate curriculum at Evergreen is organized around six major Planning Units: Scientific Inquiry; Culture, Text and Language; Expressive Arts; Environmental Studies; Society, Politics, Behavior, and Change; and Evening and Weekend Studies. The Native American, World Indigenous peoples center also offers programs each year and houses the Reservation Based/Community Determined Program that offers programs in Native communities in the western half of the state. In addition the Tacoma Program serves upper division students in Tacoma and is discussed separately. Each planning unit is responsible for developing and introductory entry point(s), sophomore level programs, into the program of study in the area and for providing a variety of more or less formally organized advanced work. In addition each area is expected to contribute twenty percent of its teaching to Core (First year) programs and inter-divisional programs each year. While the formal structure of the areas is similar, the areas vary considerably in the extent to which they are formally organized around repeated offerings, the degree of demand they put on their members to teach within the area’s offerings, and the degree to which advanced work is formally identified.

Each faculty member is affiliated with one planning unit. This affiliation usually, but not always, reflects their professional training. Faculty members can and occasionally do change their affiliation as their interests and capacities change. Planning units themselves occasionally change their focus or reorganize. Planning Units select a Coordinator (PUC) from among their ranks to organize and conduct meetings and coordinate with other units and the Curriculum Dean. Planning units can be distinguished from departments by their lack of budget, lack of permanent assigned faculty lines, and their lack of control over the hiring of new faculty. They are based on a strange amalgam of faculty autonomy and collective suasion. Planning units are the current answer to the question of how the college should organize the faculty into coherent groups for planning curriculum. This question has been an on-going issue at the college. Finding a balance between stability in the curriculum and freedom to investigate and explore issues that engage the faculty’s attention and concern has been a necessary and continuing tension. In the past few years concerns about this structure have motivated considerable discussion and debate on the campus.

Modes of Study

While the single most important structure for offering the curriculum is the coordinated studies program described above. Several other modes of study are used. The single faculty member program offers a specific piece of full-time study for one to three quarters. This format is usually used for offering advanced work in a wide variety of disciplines. Half-time coordinated studies programs are the foundation of the evening and weekend program. Like full time programs they can be offered for one to thee quarters. The evening and weekend program also offers a range of courses designed to stand on their own or to be supplementary to other offerings. Individual contracts and internships are offered. Such contracts are most frequently for advanced work. Internship Learning contracts are agreements between the student, an internship field supervisor, the school, and a faculty member. They are most frequently undertaken as an individual study, but may be required as a part of the work within a coordinated study of group contract. Both internship learning contracts and Individual Contracts are reviewed and signed off on by the Academic Deans.

Curriculum Planning

The undergraduate curriculum at Evergreen is a complex mixture of regularly repeating offerings, irregularly repeating offerings, and one time efforts. The curriculum is revised annually. Each planning unit is responsible for defining and staffing its offerings and is expected to contribute 20% of its faculty time in each year to Core (First-Year) programs and another 20% to inter-divisional program work. Planning in any given year is designed to develop a catalogue for two years hence. Thus in the 2008-9 school year faculty will be designing the curriculum for the 2010-11 school year. The curriculum dean(s) in collaboration with the PUCs organize a series of all faculty meeting in early part of fall quarter that are designed to solicit ideas, proposals, and suggestions for interdivisional work at the First Year and above level.

Usually planning units meet at the fall faculty retreat and in the latter half of the quarter to identify their on-going staffing needs and identify planning unit members interested in working in inter-area and Core. These meeting involve looking at the curriculum of the unit over a four year period, the year being planned, the current year, the next year and usually consider the year following the year being planned for. This iterative retrospective-prospective overview helps identify the needs for prerequisites, help identify the appropriate cycle year for regularly, but not annually, repeating programs, identify questions of balance in subject matter, and clarify individual contributions to the units’ work. It is inside of planning units that most of the on-going repeated offerings of the college are planned and much, but by no means all, of the advanced work offered is planned.

Simultaneously Core and inter-divisional planning which began early in the fall with the meeting to share ideas continues more or less informally as faculty follow up ideas with each other and attend meetings called by either the Core dean or the Curriculum dean to start to firm up and identify programs. In addition to the intricate matchmaking that occurs within program teams, the PUCs and curriculum deans are involved in a complex process of informal negotiation and planning to ensure the appropriate number of first year seats (those in Core and then those seats identified for freshmen in all-level or lower-division programs) and appropriate coverage of planning unit repeated offerings. All of these decisions are made in negotiations among faculty and deans and are vetted to the planning unit meetings in winter quarter so that faculty can evaluate and respond to the area’s curriculum and its relation to other Core and inter-area offerings. This complex two-tracked process within and between the planning units culminates in a draft curriculum by the end of winter quarter. The final negotiations between Planning Units and the deans, the creation of catalogue copy for programs and the identification of staffing needs is carried out by PUCs who are given release time in spring quarter.

First Year Programs and Options

Freshman students at Evergreen may enter a diverse array of programs. The three most important choices available to them are Core programs designed explicitly for freshmen and All-Level programs in which a percentage, usually twenty-five percent of the seats, are reserved for freshmen, and introductory/lower division programs where as many as 50 percent of the seats are reserved for first year students. All-level programs that cater to the largest numbers are often, though not always inter-area programs that involve faculty form two or more planning units.

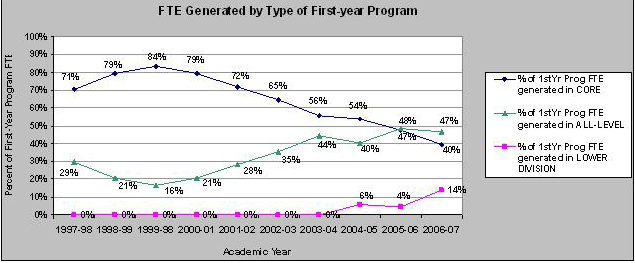

Core programs are designed explicitly for freshman students. They are almost always interdisciplinary and frequently interdivisional offerings involving two to four faculty members and often are taught for two quarters or a full year. They are distinguished by slightly smaller faculty student ratio (1/23), a strong collaborative relationship with Academic Advising, and extensive support from the Writing and Quantitative Reasoning center as appropriate. The primary virtue of the broadly interdivisional core programs is the provision of a broad base from which a student may develop her college education. These programs are usually thematically organized and provide a wide ranging often quite sophisticated inter-disciplinary perspective on contemporary and historical questions of human experience. All Core programs do work explicitly on materials that support general education and the development of skills in writing, reading, seminar participation, collaborative work more generally, and critical thinking. In many programs quantitative reasoning, library research, field research skills of various sorts are supported as well. In recent years there has been a tendency for narrower two person programs, the difficulty that arises when the number of faculty members in a program shrinks to as few as two is that the breadth of the offerings may suffer. In the first years of this review period 1997-98 and 1998-99 many and often most Core programs lasted through three full quarters. Today most programs are one or two quarters long. (Catalogue 1997-98,1998-99, 2005-6, 2006-7) For many years Core programs were the preponderant first year experience, today, fewer than half of all first year students get this sort of support. Indeed there has been a marked shift in terms of where first-year slots are located in the full-time curriculum. Over this period, a growing proportion of first-years enrolled in All-level program seats (programs which enroll freshmen through seniors) compared to Core programs (targeted at freshmen and new first-time, first-year students). In AY 1997-98, 71% of first-year program FTE was generated in Core programs, but by AY 2006-07, only 40% was generated in Core. Lower-division programs (which enroll freshmen and sophomores) began to appear in AY 2004-05. By AY 2006-07, lower-division programs represented 14% of all first-year program FTE.

In the beginning of the college all programs were all-level, while that model went by the boards in many areas, the idea that students at all points in their education could usefully work together persisted in some areas, notably CTL. The concept of all level programs was also supported by the emphasis on inter-area programs that, like core, were supposed to constitute 20 % of the curriculum and be planned on a year-by-year basis. Because such programs are supposed to be attractive and available to students with quite different educational backgrounds most even when they included art or science do not have prerequisites. All-level programs usually provide less systematic support for freshmen students, but offer a challenge to some of the better prepared freshman students who want to work in what is often a more demanding environment. Nevertheless they are often, though not always, quite broad, and tend to provide opportunity for developing a good foundation for more advanced work.

Finally, some areas have opened up lower division programs or introductory programs to allow some (often as many as half) of the students to be freshmen. The argument for this kind of work in the first year is centered on the desire that many students have to get into the subject matter that draws them to college in the first place. Again this had significant advantages for some students in as much as they are directly challenged and engaged in material that they find important. Yet such a program often does not provide the range of support for more general skills nor doe it provide the kind of inter-divisional breadth that is desirable.

Historically, Core programs have been among the broadest and most thoroughgoing interdisciplinary programs on campus. In theory, but not always in practice, they are supposed to occupy a priority position in the planning process. A major tension exists in the planning process between the process of planning Core programs that tend to be ad hoc in any given year and the systematic planning of many Planning Units that attempt to stabilize and identify curricular paths some years into the future. This tension has lead to two major developments over the past-ten years. First as areas have attempted to both provide twenty percent of the seats taught by their faculty as freshman seats, Planning Units have attempted to serve both Planning Unit needs and freshman seat needs by moving introductory Planning Unit offerings into lower division work thus opening introductory lower division offerings to large numbers of freshman students. Alternatively areas and individual faculty members have attempted to meet their collective/personal obligation to provide freshman seats by declaring their program all level and allocating 25% or more of their seats to freshmen without significant modification of their content. Both of these tendencies are supported by the switch some years ago form planning units being responsible for providing faculty to teach in Core to being responsible to provide twenty percent of the seats taught by their faculty as available to freshmen. To the extent that these programs are intra-area programs the pool of faculty available for inter-divisional team teaching is diminished.

In recent years both recruiting faculty to teach in Core programs and creating effective social and intellectual social times and places for inter-divisional teams and plans to emerge has been a serious issue for the college. These difficulties rest in some measure on the ambiguity of whether the obligation to teach in core rests on individual faculty or on the Planning Unit. Prior to 1995 curriculum revision, the obligation rested ambiguously, but decidedly with the faculty. Faculty members were expected to teach Core one out of four years. Today the burden is often presumed to lie with the area and teaching in core is seen in some areas a scheduled assignment. The difficulty in forming teams rests on the retirement of experienced faculty, the recruitment of newer faculty who have been impressed into service in the Planning Units, and the difficulty in developing planning and social time that underlies the possibility of making effective intellectual matches that lead to broad effective teaching teams. The ability to plan long range complex programs is exacerbated by the growing tendency to reduce teaching assignments to smaller and smaller bits thus increasing the need for immediate short term planning time and increasing the experienced workload of faculty.

Several issues arise around the First year experience.

First has to do with the perception of Core programs by incoming students. Core programs can be and often are demanding and academically rigorous programs. Yet they are often seen by incoming freshmen as less demanding than lower division or all level programs. The attempts to develop skills and introduce the college while appreciated and useful to some are seen as hand holding and dumbing down by others. To the extent that Core programs are not rigorous and demanding or to the extent that they are not matching particular student’s interest they are often described as boring.

Second, fall to fall retention is a serious issue for the college in its first year offerings. While there are numerous arguments for why a less than stellar retention rate might exist at the college, the problem is a serious one. The matching of students to their choices within first year programs is surely a contributor to this problem. Ironically as we open more choices to students the number of students getting their first choice has dropped as many of the choices in advanced and all level programs represent very few seats.

Recruiting engaged and committed faculty teams, finding enough time to develop effective teaching themes and plans, providing opportunities to reflect on those experiences, and developing both intellectual and pedagogical skills is crucial to making teaching first year students worthwhile and intellectually rewarding for facultyand students alike. This almost of necessity requires a new recruitment and planning structure that can sustain faculty engagement with interdisciplinary issues and concerns over time.

Inter-Area Programs

Inter-area programs are another class of inter-disciplinary programs offered. Like Core programs they involve faculty from two or more planning units offering programs which deal with a theme or question, but are designed for students at upper division, sophomore and above, or all level. By design students typically bring a distinctly mixed background to these programs, not only in terms of years of college experience but also in terms of specialization and interests. Inter-area programs are a primary location for the teaching of general education skills. Inter-area programs often involve faculty with quite different skill sets to programs. They tend to teach some aspect of these distinct capacities in the program. Thus inter-area programs were a primary location where faculty with particular skills in quantitative reasoning, mathematics and art were able to share this information with students who typically avoided such learning. Thus between 65% and 85% of inter area programs in the 2001- 2 to 2005-6 end of program reviews reported some emphasis on mathematics. While 60-80% of the programs in the same period reported an emphasis on art. (Institutional Research, End of Program Review 2001-02 -2005-6 Art in Programs and Mathematics and Science in Programs. 2006) In recent years inter-area programs have frequently been all-level and have through this mechanism contributed a very significant number of freshman seats. Indeed a significant migration of interdivisional work from Core to Inter-Area all level teaching has occurred over the past ten years. According to the 1995-6 Long Range curriculum plan planning units were expected to contribute 20 % of their teaching effort to both Core and Inter-area programs. That goal was seldom reached in between 1997-98 AY and 2000-01AY but has been the norm since that time, with the proportion of Core Programs shrinking consistently. (Institutional Research, Updated Curricular visions Table 2 Olympia Full time Program FTE Distribution, 2007)

Individual Contracts and Internships

Individual Contracts and internships allow students to follow their passions, define their own work, and expand their opportunities beyond the walls of the college in very important ways. Developing and negotiating a contracts with faculty and in internships field supervisors, forces a kind of reflective thinking about their work and compels students to take responsibility for their won education as they move into doing advanced work. Work with faculty though often limited is very different and more personal from working in the confines of a program. These modes of learning are the ultimate mode of taking responsibility for your own education.

Internships provide opportunities for students to gain exposure to work experience, applications of lessons learned in class to real world applications, and chance to learn about the complexities, skills, and culture of a potential work place. Internships involve a complex three-way negotiation between a student, a field supervisor at a job site and a member of the faculty. Students work with Academic Advising and increasingly with the Center for Community Based Learning and Action to identify internships that extend their studies. The work of this Center both serves students by locating activities and also provides a more regular a systematic conduit for student volunteers into community work. The Center has been particularly useful in helping facilitate volunteer and internship activity for work within programs. Negotiations between the student, faculty, and the field supervisor are supported by Academic Advising identify the goals of the internship experience, the amount of credit earned, the academic work that accompanies the internship, the work undertaken, the reporting lines, and identifies the role of the field supervisor, faculty member and student in evaluation of the student’s work. Internships are undertaken by students at different points in their education. The longer more substantial internships such as legislative internships or work within a social service agency are usually undertaken in the junior or senior year. Shorter internships are often directed toward community service work. Students undertook 506 internships in the in the 2006-7 school year with 26% in fall, 36% in winter, and 38% in spring. In most instances Internship work constituted a portion of the student’s work as the 401 FTE generated by these internships attests. Internships have proven to be valuable as a way of linking the college into the broader community, helpful in locating work experience that supports student transition into the workplace after graduation, and an opportunity for students to prepare and design important components of their education.

Individual contracts are critical elements in the education of many students at the college. They allow for advanced work, they accommodate idiosyncratic life situations, and they provide opportunities for student initiative. Consultation with the Academic Deans who read and approve all contracts and internship reveals that contracts serve two very different functions. The first and most important function is as a location for students to undertake significant usually advanced independent research or inquiry. The second is as a stopgap measure that accommodates a student’s schedule, life circumstance, or inability to get in to work within programs that they want or need. Typically, but not always the former are more effective, more carefully thought through, and provide more demonstration of learning than the latter. Student’s can write individual contracts for 2 to 16 quarter hours credit. Usually smaller contracts supplement work in a part-time program or are useful in providing a small piece of prerequisite learning for admission to a future program or graduate school.

In 2006-7 Students and faculty wrote a total of 1279 Individual Learning Contracts 300 in fall, 454 in winter, and 525 in spring. These contracts generated approximately 922 FTE. Contracts and internships together generated some 1322.8 FTE during the year.

In good contracts students need to define what they want to learn, they need to have a background that will allow them to deal with the project, they need to define the activities that will help them learn, and they need to be able to demonstrate that learning. Coherence between the learning objectives of the contract and the activities they undertake is the central issue. The deans report that a significant majority of contracts are reasonably well developed and define substantial individual work that coherently defines learning objectives and the work undertaken.

Prior Learning from Experience

The Prior Learning from Experience Program faculty assesses the student's past academic experience and past life experience before recommending Evergreen's PLE program. The full time staff position was cut from the budget in spring of 2003 and the program was reorganized into the Evening Weekend curriculum. The coordinator from the previous staff position was moved into the adjunct faculty position. The adjunct faculty forms teams of full-time continuing faculty to assess the PLE documents. A central tenet of Evergreen's PLE program is that credit is granted for learning and not for experience. Students must document that learning by drawing on current theories in particular academic fields. They accomplish this by interviewing appropriate faculty about their documents and completing necessary research. Because faculty members grant credit for PLE documents, they grant credit only for learning which would normally occur within regular curricular offerings.

The documentation currently required for credit through PLE at Evergreen is rigorous. Most interested students, beginning in fall of 2003, take "Writing from Life", a course taught by the adjunct faculty. Course requirements include writing an autobiography, their PLE document outline, and one learning essay or chapter of their PLE document. Students then move into PLE document writing (taught by the same adjunct faculty) the following quarter and take that course for 4, 6, or 8 credits until they have earned 16 credits. At that time their essay writing is finished and they are ready for a faculty review. All students include a resume, an autobiography, a narrative description of their learning, and appendixes documenting that learning such as reports or guidelines the student developed. Faculty reviewing the PLE process found the documentation to be generally more demanding than other undergraduate credit they awarded.

Evergreen awards up to a maximum of forty-five PLE credits, but sixteen of those forty-five are earned in PLE document writing. They can be awarded any additional credit above 16 to achieve the full forty-five but most are awarded less than that. Students are not assured of receiving the credit that they may expect at any time in this process. Credit is identified as PLE via the narrative evaluation of the student's work.

The Prior Learning adjunct faculty ensures that any credit requested does not duplicate credit already on the student's transcript. After the faculty team awards credit they notify the Dean of the adjunct faculty's assistant and the assistant finalizes the evaluation and notifies student accounts whom then bills the student for the credit awarded. The student then pays for the credit and the credit is officially granted and the evaluation is entered into the student's transcript.