Difference between revisions of "Standard 2"

(→MIT - Graduate Records and Academic Credit (Standard 2.F)) |

(→MES Faculty and Related Resources (Standard 2.E)) |

||

| (214 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | ==Standard 2 | + | ==Standard 2 – Educational Program and Its Effectiveness== |

| + | [[Image:two_science.jpg]] | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

''The institution offers collegiate level programs that culminate in identified student competencies and lead to degrees or certificates in recognized fields of study. The achievement and maintenance of high quality programs is the primary responsibility of an accredited institution; hence, the evaluation of educational programs and their continuous improvement is an ongoing responsibility. As conditions and needs change, the institution continually redefines for itself the elements that result in educational programs of high quality.'' | ''The institution offers collegiate level programs that culminate in identified student competencies and lead to degrees or certificates in recognized fields of study. The achievement and maintenance of high quality programs is the primary responsibility of an accredited institution; hence, the evaluation of educational programs and their continuous improvement is an ongoing responsibility. As conditions and needs change, the institution continually redefines for itself the elements that result in educational programs of high quality.'' | ||

| Line 6: | Line 8: | ||

Evergreen's strategic plan identifies the college as unique in American higher education, locating itself as “the nation’s leading public interdisciplinary liberal arts college.” Since the early years of the college, Evergreen has expected students to assume significant responsibility for their learning. They were expected to define their own work and design their own course of study from the opportunities offered by the faculty in programs (full-time learning communities) and through work designed with individual faculty members. This concept of the student differed sharply from the one presupposed by both large public universities and small private colleges. The new college in Olympia would offer a reinvigorated liberal arts teaching for all. The college’s commitment to interdisciplinarity, student engagement, and collaboration rests on this vision of an inclusive, public, egalitarian liberal arts education. | Evergreen's strategic plan identifies the college as unique in American higher education, locating itself as “the nation’s leading public interdisciplinary liberal arts college.” Since the early years of the college, Evergreen has expected students to assume significant responsibility for their learning. They were expected to define their own work and design their own course of study from the opportunities offered by the faculty in programs (full-time learning communities) and through work designed with individual faculty members. This concept of the student differed sharply from the one presupposed by both large public universities and small private colleges. The new college in Olympia would offer a reinvigorated liberal arts teaching for all. The college’s commitment to interdisciplinarity, student engagement, and collaboration rests on this vision of an inclusive, public, egalitarian liberal arts education. | ||

| − | Evergreen traces its origins to debates within higher education in the 1960s and 1970s. | + | Evergreen traces its origins to debates within higher education in the 1960s and 1970s. These debates involve two quite distinct critiques that contributed profoundly to the college’s pedagogical assumptions and practices. First came a critique of the multiversity, the large-scale public multi-disciplinary institution that blossomed in the post-war years. From the point of view of this critique, most forcefully embodied in the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, the multiversity existed primarily for the benefit of corporate/governmental interests. It functioned to maintain a supply of useful technicians and professionals. This critique saw the public university as serving class interests rather than living up to the ideals of a democratic educational system that would educate citizens broadly. The second critique assessed the liberal arts tradition as manifested in the small private liberal arts colleges. This critique began with the stodginess and irrelevance of the canon, and the unwillingness of liberal arts colleges to take on the issues of race, class, war, and revolution. This critique centered on the failure of the liberal arts colleges collectively to act on their own professed values as they distanced themselves from the world of action. In the face of the crisis of civil rights, the Vietnam war, and questions of class privilege the liberal arts were stuck defending texts, traditions, and positions that did not question the status quo. The critique of the multiversity questioned the failure of democratic education and the lack of moral judgment about public policy. The critique of the small liberal arts college viewed the moral tradition and ethical questions as outdated, abstracted from the world, and hence irrelevant. These debates in the context of the turmoil of the times made it possible for such important moderates as then Governor Dan Evans and State Senator Gordon Sandison to call for a new college that would take a new and alternative approach to college education. |

The founding faculty of Evergreen, for the most part men in their thirties and early forties, envisioned a college that, above all, was engaging. They wanted a public college that could provide the best elements of the liberal arts college – a college that could acknowledge and deal with ethical issues, one which saw the world as intellectually comprehensible and one which offered students opportunities to learn and to act for the good of the community, not simply for individual or corporate aggrandizement. In the planning year, the work of Alexander Meiklejohn, Joseph Tussman, and John Dewey provided models of educational reform that took intellectual rigor and public engagement as fundamental goals. In short, they believed in public education as a public good. They hoped for an education that would support action, engagement, and collaboration with diverse others; an education within a meaningful community context. They created an education that offered opportunities and curricular structures geared to engaged learning, not passivity. They wanted students to take control of their own education, to make real value-centered coherent choices about what they learned, how they learned, and what they did with the education they received. At the heart of these desires was a passionate debate about concern for authentic learning. All of the above characterizations of the college were contested, but in the crafting of the structure, a template the college has been tinkering with and transforming ever since, these were central values. | The founding faculty of Evergreen, for the most part men in their thirties and early forties, envisioned a college that, above all, was engaging. They wanted a public college that could provide the best elements of the liberal arts college – a college that could acknowledge and deal with ethical issues, one which saw the world as intellectually comprehensible and one which offered students opportunities to learn and to act for the good of the community, not simply for individual or corporate aggrandizement. In the planning year, the work of Alexander Meiklejohn, Joseph Tussman, and John Dewey provided models of educational reform that took intellectual rigor and public engagement as fundamental goals. In short, they believed in public education as a public good. They hoped for an education that would support action, engagement, and collaboration with diverse others; an education within a meaningful community context. They created an education that offered opportunities and curricular structures geared to engaged learning, not passivity. They wanted students to take control of their own education, to make real value-centered coherent choices about what they learned, how they learned, and what they did with the education they received. At the heart of these desires was a passionate debate about concern for authentic learning. All of the above characterizations of the college were contested, but in the crafting of the structure, a template the college has been tinkering with and transforming ever since, these were central values. | ||

| Line 12: | Line 14: | ||

As was argued in the opening pages of this self-study, the president and the founding faculty wanted to create a public college devoted to teaching and learning in an interdisciplinary, collaborative framework within which students must exercise autonomy and judgment. Charles McCann’s four nos – no academic departments, no faculty ranks, no academic requirements, and no grades – were seen as a vehicle to liberate faculty and students. The lack of departments and ranks allowed faculty to work and collaborate across disciplinary boundaries and across differences in age and experience. The lack of requirements and grades freed students to work together to share and collectively create their learning without endangering their own class standing. Collaboration, not competition, became the fundamental vehicle for organizing teaching and learning. While within the college the breadth of the challenge to the conventions of higher education was reasonably well understood, the external world tended to know the college in its first decades primarily on the basis of the above negatives and on the basis of the inevitable conflation of long hair, protest, and defiant optimism with a hippie haven and/or radical protest. | As was argued in the opening pages of this self-study, the president and the founding faculty wanted to create a public college devoted to teaching and learning in an interdisciplinary, collaborative framework within which students must exercise autonomy and judgment. Charles McCann’s four nos – no academic departments, no faculty ranks, no academic requirements, and no grades – were seen as a vehicle to liberate faculty and students. The lack of departments and ranks allowed faculty to work and collaborate across disciplinary boundaries and across differences in age and experience. The lack of requirements and grades freed students to work together to share and collectively create their learning without endangering their own class standing. Collaboration, not competition, became the fundamental vehicle for organizing teaching and learning. While within the college the breadth of the challenge to the conventions of higher education was reasonably well understood, the external world tended to know the college in its first decades primarily on the basis of the above negatives and on the basis of the inevitable conflation of long hair, protest, and defiant optimism with a hippie haven and/or radical protest. | ||

| − | It is in this context of extraordinary student and faculty autonomy that the college has developed. The individual student is responsible for the content of his or her degree. The faculty, while they exercise significant control over the work of students in programs, frames its desires for the overall outcomes of student work at the college in terms of expectation rather than requirements. As part of the response to the last round of accreditation the college developed | + | It is in this context of extraordinary student and faculty autonomy that the college has developed. The individual student is responsible for the content of his or her degree. The faculty, while they exercise significant control over the work of students in programs, frames its desires for the overall outcomes of student work at the college in terms of expectation rather than requirements. As part of the response to the last round of accreditation the college developed Six Expectations of an Evergreen Graduate: |

* to articulate and assume responsibility for your own work; | * to articulate and assume responsibility for your own work; | ||

| Line 24: | Line 26: | ||

| − | ===Standard 2.A | + | ===Standard 2.A – General Requirements=== |

| − | ====2.A.1 | + | ====2.A.1 Institutional Support to Academics==== |

''The institution demonstrates its commitment to high standards of teaching and learning by providing sufficient human, physical, and financial resources to support its educational programs and to facilitate student achievement of program objectives whenever and however they are offered.'' | ''The institution demonstrates its commitment to high standards of teaching and learning by providing sufficient human, physical, and financial resources to support its educational programs and to facilitate student achievement of program objectives whenever and however they are offered.'' | ||

| Line 33: | Line 35: | ||

Academic offerings are supported by faculty, facilities, equipment, and staff support. | Academic offerings are supported by faculty, facilities, equipment, and staff support. | ||

| − | Facilities supporting academics | + | Facilities supporting academics include teaching spaces and offices. Each faculty member teaching half-time or more is provided an office. Those teaching less than half-time may be allocated a shared office space. Faculty offices average 140 square feet, in accord with state standards. |

Faculty are allocated computers, software, and peripherals in accordance with their teaching and professional development needs. Regular faculty are provided new computers with a turnover rate that averages four years. Visitors and adjuncts are provided reassigned computers from inventory when possible or new computers if adequate computers are not available. Faculty and academic staff computers are funded from a dedicated summer school revenues pool that provides $225,000 per year for this purpose. Due to the wide range in computing needs, faculty request and receive a variety of computers: laptops, desktops, Apple, PC, high-end processors, and more standard configurations. This also applies to software and peripherals. | Faculty are allocated computers, software, and peripherals in accordance with their teaching and professional development needs. Regular faculty are provided new computers with a turnover rate that averages four years. Visitors and adjuncts are provided reassigned computers from inventory when possible or new computers if adequate computers are not available. Faculty and academic staff computers are funded from a dedicated summer school revenues pool that provides $225,000 per year for this purpose. Due to the wide range in computing needs, faculty request and receive a variety of computers: laptops, desktops, Apple, PC, high-end processors, and more standard configurations. This also applies to software and peripherals. | ||

| − | In addition to individual faculty resources, space and equipment are also provided for specialized facilities including computer labs, media labs, science labs, art studios, performance spaces, galleries, research space, etc. The college has a dedicated equipment fund of approximately $250,000 per year, often supplemented by additional funds when special initiatives, such as renovations, warrant it. Each year academics, like other divisional units across the campus, identifies new and replacement equipment needs that support the curriculum. These lists are prioritized in a master list for funding. In general, roughly one-third of the equipment requested by the academic division in any given year is actually funded. This is sufficient to meet the most critical curricular needs, but not enough to provide anywhere near all of the equipment requested. | + | In addition to individual faculty resources, space and equipment are also provided for specialized facilities including computer labs, media labs, science labs, art studios, performance spaces, galleries, research space, etc. The college has a dedicated equipment fund of approximately $250,000 per year, often supplemented by additional funds when special initiatives, such as renovations, warrant it. Each year academics, like other divisional units across the campus, identifies new and replacement equipment needs that support the curriculum. These lists are prioritized in a master list for funding. In general, roughly one-third of the equipment requested by the academic division in any given year is actually funded. This is sufficient to meet the most critical curricular needs, but not enough to provide anywhere near all of the equipment requested. The college depends on equipment grants to partially or completely fund the most expensive equipment. Faculty collaborate with the grants office to pursue this funding. |

| − | + | ||

| − | The college depends on equipment grants to partially or completely fund the most expensive equipment. Faculty collaborate with the grants office to pursue this funding. | + | |

Each academic program is also awarded a budget based on the number of students expected to enroll and the kind of goods and services that will be needed to deliver the curriculum. Program faculty complete budget requests that include expenses for photocopying, honoraria for guest speakers, supplies, motor pool vans for field trips, film/video rentals, laboratory and studio expenses, etc. Programs anticipating higher-than-usual expenses, such as those with an international travel component, may include additional support in their request. | Each academic program is also awarded a budget based on the number of students expected to enroll and the kind of goods and services that will be needed to deliver the curriculum. Program faculty complete budget requests that include expenses for photocopying, honoraria for guest speakers, supplies, motor pool vans for field trips, film/video rentals, laboratory and studio expenses, etc. Programs anticipating higher-than-usual expenses, such as those with an international travel component, may include additional support in their request. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

Approximately $340,000 per year is available for program budgets. This is on average two-thirds of the total requests from the faculty. There is an additional budget of $300,000 to fund student aides in support of academic programs. These budgets are divided among approximately 150 academic programs during the academic year (Summer School, Tacoma, Graduate Programs and the Reservation-Based program have their own budgets for program support). This provides approximately $40/student/quarter (ranging from $300/student/quarter to $10/student/quarter) in direct academic program support. This may appear high, but one needs to bear in mind that the Evergreen academic program operates in a very decentralized mode; without departments, there is little budgetary structure between the organizational top and the individual faculty member or faculty team. Hence, faculty are given direct control over the many resources required to support their academic program. In most cases, these resources prove to be adequate for the goals faculty have in mind. | Approximately $340,000 per year is available for program budgets. This is on average two-thirds of the total requests from the faculty. There is an additional budget of $300,000 to fund student aides in support of academic programs. These budgets are divided among approximately 150 academic programs during the academic year (Summer School, Tacoma, Graduate Programs and the Reservation-Based program have their own budgets for program support). This provides approximately $40/student/quarter (ranging from $300/student/quarter to $10/student/quarter) in direct academic program support. This may appear high, but one needs to bear in mind that the Evergreen academic program operates in a very decentralized mode; without departments, there is little budgetary structure between the organizational top and the individual faculty member or faculty team. Hence, faculty are given direct control over the many resources required to support their academic program. In most cases, these resources prove to be adequate for the goals faculty have in mind. | ||

| − | A number of academic support services are centralized including academic budgeting, support for travel, institutional research, and grants. Professional staff provide technical support for both the arts and sciences, and these are budgeted through the Provost’s office. Again, this support is typically adequate although demand for this support varies from quarter to quarter and year to year depending on the curricular offerings. Faculty are assigned program secretaries that support the narrative evaluation process and provide administrative support to program activities. | + | A number of academic support services are centralized, including academic budgeting, support for travel, institutional research, and grants. Professional staff provide technical support for both the arts and sciences, and these are budgeted through the Provost’s office. Again, this support is typically adequate although demand for this support varies from quarter to quarter and year to year depending on the curricular offerings. Faculty are assigned program secretaries that support the narrative evaluation process and provide administrative support to program activities. |

Programs at off-campus sites (Tacoma and the Reservation-Based programs) are an integral part of the college's offerings, and are supported at the same or higher level. | Programs at off-campus sites (Tacoma and the Reservation-Based programs) are an integral part of the college's offerings, and are supported at the same or higher level. | ||

| − | ====2.A.2 | + | ====2.A.2 Educational Goals==== |

''The goals of the institution’s educational programs, whenever and however offered, including instructional policies, methods, and delivery systems, are compatible with the institution’s mission. They are developed, approved, and periodically evaluated under established institutional policies and procedures through a clearly defined process.'' | ''The goals of the institution’s educational programs, whenever and however offered, including instructional policies, methods, and delivery systems, are compatible with the institution’s mission. They are developed, approved, and periodically evaluated under established institutional policies and procedures through a clearly defined process.'' | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

In the work leading to the college’s first strategic plan and in the 1988 self-study for accreditation, the ''Five Foci of an Evergreen Education'' were first enunciated. They have served the college well over the years as a central articulation of its mission. The following section lays out the five foci and articulates the ways in which these foci are implicated by the work of reflexive thinking, and lead the educational practices of the college. | In the work leading to the college’s first strategic plan and in the 1988 self-study for accreditation, the ''Five Foci of an Evergreen Education'' were first enunciated. They have served the college well over the years as a central articulation of its mission. The following section lays out the five foci and articulates the ways in which these foci are implicated by the work of reflexive thinking, and lead the educational practices of the college. | ||

| − | The Five Foci of an Evergreen Education – interdisciplinary study, personal engagement in learning, linking theory with practice, collaborative/cooperative work, and teaching across significant differences – have played a central role in creating both a curriculum and a rationale for a curriculum. They inform both the programs and our articulation of them at all levels of the institution. These foci capture much, but not all of what is done at Evergreen. Many of our actual activities contribute to more than one focus. | + | The Five Foci of an Evergreen Education – interdisciplinary study, personal engagement in learning, linking theory with practice, collaborative/cooperative work, and teaching across significant differences – have played a central role in creating both a curriculum and a rationale for a curriculum. They inform both the programs and our articulation of them at all levels of the institution. These foci capture much, but not all, of what is done at Evergreen. Many of our actual activities contribute to more than one focus. |

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

Interdisciplinary study is fundamental at Evergreen. At the heart of such study is the intellectual conviction that academic disciplines have limits inherent in their epistemology, their explanatory concepts, and the like and that, in the presence of complex phenomena, the inadequacy of isolated accounts from different disciplines is revealed. Seldom if ever are the accounts of any one discipline all that can or needs to be said about such phenomena. Further, the attempt to understand phenomena apart from their context in the world often simply misses the critical importance of the phenomena and their meaning. For us to know complexly and think reflexively demands that we see from diverse perspectives and ask our own questions of the phenomena we study. An interdisciplinary approach provides students with at least three crucial intellectual understandings that help them recognize their perspectives and generate their questions. First, different disciplines can indeed hold different and valid understandings about a particular phenomenon. Interdisciplinary thinking pushes students beyond a disciplinary understanding and forces them to complicate and contextualize their views of what is at issue. Second, interdisciplinary study illustrates the ways in which different disciplines illuminate differing aspects of reality, thus extending and complicating student views of what a phenomenon actually is. Finally, an interdisciplinary understanding more accurately reflects the world as students encounter it in internships, volunteer service, and field research. The significance of interdisciplinary work and the ways in which it supports students as they move beyond Evergreen is echoed in alumni survey data and qualitative accounts. | Interdisciplinary study is fundamental at Evergreen. At the heart of such study is the intellectual conviction that academic disciplines have limits inherent in their epistemology, their explanatory concepts, and the like and that, in the presence of complex phenomena, the inadequacy of isolated accounts from different disciplines is revealed. Seldom if ever are the accounts of any one discipline all that can or needs to be said about such phenomena. Further, the attempt to understand phenomena apart from their context in the world often simply misses the critical importance of the phenomena and their meaning. For us to know complexly and think reflexively demands that we see from diverse perspectives and ask our own questions of the phenomena we study. An interdisciplinary approach provides students with at least three crucial intellectual understandings that help them recognize their perspectives and generate their questions. First, different disciplines can indeed hold different and valid understandings about a particular phenomenon. Interdisciplinary thinking pushes students beyond a disciplinary understanding and forces them to complicate and contextualize their views of what is at issue. Second, interdisciplinary study illustrates the ways in which different disciplines illuminate differing aspects of reality, thus extending and complicating student views of what a phenomenon actually is. Finally, an interdisciplinary understanding more accurately reflects the world as students encounter it in internships, volunteer service, and field research. The significance of interdisciplinary work and the ways in which it supports students as they move beyond Evergreen is echoed in alumni survey data and qualitative accounts. | ||

| − | There is little orthodoxy about which church of interdisciplinarity Evergreen faculty members attend. Acolytes of instrumental multi-disciplinary, thematic study, project-based experience and more teach at the college, yet nearly all agree that interdisciplinary work provides the essential pattern that allows for the emergence of connections, the creation of new kinds of understandings, and ultimately the possibility for students to find their own way to work in the curriculum. Students experience interdisciplinarity in a variety of ways, but at the center is the sense that the pieces of work that they are asked to do within a program fit together in complex and surprising ways | + | There is little orthodoxy about which church of interdisciplinarity Evergreen faculty members attend. Acolytes of instrumental multi-disciplinary, thematic study, project-based experience and more teach at the college, yet nearly all agree that interdisciplinary work provides the essential pattern that allows for the emergence of connections, the creation of new kinds of understandings, and ultimately the possibility for students to find their own way to work in the curriculum. Students experience interdisciplinarity in a variety of ways, but at the center is the sense that the pieces of work that they are asked to do within a program fit together in complex and surprising ways ([[Media: student focus group_standard2_7feb08.pdf|Student Focus Group - Standard 2 - Feb 7, 2008]]). Faculty, as they become effective as interdisciplinary teachers, retain skills and competencies they brought with them to the college and expand into new competencies and connections as they work and learn with colleagues and students over the years (David Marr, Personal Comments 2/08). All that is interdisciplinary is not team teaching and vice versa. Individual faculty members often expose students to more than one discipline and single programs with two faculty members with similar backgrounds may or may not be interdisciplinary. |

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

The founders of Evergreen wanted to create a college where students felt deeply engaged with the process and substance of learning. At its heart, personal engagement in learning was understood to be the students’ development of a capacity to know, to speak, and to act on the basis of their own self-conscious beliefs, understandings, and commitments. The reflexive capacity to think about one's own work that emerges and develops throughout a student’s engagement with the material and other people over time is central to their sense of commitment. The emphasis on participation, on reasoned evaluation and involvement in their own, their colleagues, and their faculty members’ work, strengthen this engagement. Engagement then is more than interest. It involves complex reflection on the significance and meaning of what we know; it reflects a concern for the consequences, effects, and implications of understanding as a part of knowing. Such engagement is supported in the college’s emphasis on full-time study for sixteen quarter-hours credit per quarter. The lack of graduation requirements compels students to make personal choices about their work. Such work in the end could be something quite conventional, such as medicine or art history or it could be rather unconventional, such as becoming a kayak maker, an independent filmmaker, or a specialty vegetable farmer. What distinguishes this work is the way the work implicates the person as whole. | The founders of Evergreen wanted to create a college where students felt deeply engaged with the process and substance of learning. At its heart, personal engagement in learning was understood to be the students’ development of a capacity to know, to speak, and to act on the basis of their own self-conscious beliefs, understandings, and commitments. The reflexive capacity to think about one's own work that emerges and develops throughout a student’s engagement with the material and other people over time is central to their sense of commitment. The emphasis on participation, on reasoned evaluation and involvement in their own, their colleagues, and their faculty members’ work, strengthen this engagement. Engagement then is more than interest. It involves complex reflection on the significance and meaning of what we know; it reflects a concern for the consequences, effects, and implications of understanding as a part of knowing. Such engagement is supported in the college’s emphasis on full-time study for sixteen quarter-hours credit per quarter. The lack of graduation requirements compels students to make personal choices about their work. Such work in the end could be something quite conventional, such as medicine or art history or it could be rather unconventional, such as becoming a kayak maker, an independent filmmaker, or a specialty vegetable farmer. What distinguishes this work is the way the work implicates the person as whole. | ||

| − | Work in programs, especially programs that extend across several quarters, is engagement in a full-time learning community. Here the relations are to the material, but also to the persons with whom one works. This conflation of persons and materials can lead to an intensification of engagement that creates powerful, shared intellectual, social, personal, and aesthetic excitement. Students discover that personal growth and engagement in a community are often complementary realities. This complex reality in which students pursue their own goals through shared endeavor and cooperation is the center of the experience of a learning community and critical to most students' experience of Evergreen. The capacity students develop to know, learn from, and accept the work of others constitutes a challenging exercise in representational thinking | + | Work in programs, especially programs that extend across several quarters, is engagement in a full-time learning community. Here the relations are to the material, but also to the persons with whom one works. This conflation of persons and materials can lead to an intensification of engagement that creates powerful, shared intellectual, social, personal, and aesthetic excitement. Students discover that personal growth and engagement in a community are often complementary realities. This complex reality in which students pursue their own goals through shared endeavor and cooperation is the center of the experience of a learning community and critical to most students' experience of Evergreen. The capacity students develop to know, learn from, and accept the work of others constitutes a challenging exercise in representational thinking – thinking through the eyes of another. |

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

* to apply qualitative, quantitative and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines; and | * to apply qualitative, quantitative and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines; and | ||

* to demonstrate depth, breadth, and synthesis of learning and the ability to reflect on personal and social significance of learning as a culmination of your education. | * to demonstrate depth, breadth, and synthesis of learning and the ability to reflect on personal and social significance of learning as a culmination of your education. | ||

| − | |||

The work students are capable of is seen as complex. They link and engage analysis from different disciplinary perspectives. They see cultural/social contexts. They communicate understandings that are significant to themselves and their society. Such an education then neither replicates the faculty, nor simply replicates the disciplines, traditions, professions, and skills that they profess. Instead, it encourages each student to ask his own questions, to test his own hypotheses, and to make new mistakes. This education is at once potentially conservative and radical. It's conservative in that the work is tested against the society and academic disciplines broadly, and radical in that it is always implicitly a challenge to existing conventions and knowledge. | The work students are capable of is seen as complex. They link and engage analysis from different disciplinary perspectives. They see cultural/social contexts. They communicate understandings that are significant to themselves and their society. Such an education then neither replicates the faculty, nor simply replicates the disciplines, traditions, professions, and skills that they profess. Instead, it encourages each student to ask his own questions, to test his own hypotheses, and to make new mistakes. This education is at once potentially conservative and radical. It's conservative in that the work is tested against the society and academic disciplines broadly, and radical in that it is always implicitly a challenge to existing conventions and knowledge. | ||

| − | At the heart of Evergreen’s understanding of education is a belief that whatever that education is in terms of substance, it should be self consciously and thoughtfully chosen by the student. Each student should see and articulate his own work in the context of engagement with others. Skills and capacities are not autonomous and instrumental, but embedded in the context of a person’s education as a whole and more broadly embedded in the social order through participation in and reflection on that order by students. Thus the fundamental goal can be seen as developing a capacity for reflexive thought on the part of students. This reflexive capacity demands both engagement with and inquiry into the world and the work of the student as an active, self-conscious participant in the world. | + | At the heart of Evergreen’s understanding of education is a belief that whatever that education is in terms of substance, it should be self-consciously and thoughtfully chosen by the student. Each student should see and articulate his own work in the context of engagement with others. Skills and capacities are not autonomous and instrumental, but embedded in the context of a person’s education as a whole and more broadly embedded in the social order through participation in and reflection on that order by students. Thus the fundamental goal can be seen as developing a capacity for reflexive thought on the part of students. This reflexive capacity demands both engagement with and inquiry into the world and the work of the student as an active, self-conscious participant in the world. |

The five foci and the six expectations are different articulations of very similar understandings about the central nature of Evergreen. The foci speak primarily to the content and nature of the curriculum offered. They articulate the emphasis on interdisciplinarity, cooperation, work across difference, the constant interplay of theory and practice, and student engagement. The six expectations are an expression of how the qualities of a curriculum organized around these ideas should be manifest in its graduates. Here is one version of the relationship of the foci and expectations: | The five foci and the six expectations are different articulations of very similar understandings about the central nature of Evergreen. The foci speak primarily to the content and nature of the curriculum offered. They articulate the emphasis on interdisciplinarity, cooperation, work across difference, the constant interplay of theory and practice, and student engagement. The six expectations are an expression of how the qualities of a curriculum organized around these ideas should be manifest in its graduates. Here is one version of the relationship of the foci and expectations: | ||

| − | Personal Engagement – Articulate and assume responsibility for your own work. Participate collaboratively and responsibly in our diverse society. Reflect on the personal and social significance of your learning. | + | '''Personal Engagement''' – Articulate and assume responsibility for your own work. Participate collaboratively and responsibly in our diverse society. Reflect on the personal and social significance of your learning. |

| − | Teaching and Learning Across Significant Difference – Participate collaboratively and effectively in our diverse society. Communicate clearly and effectively. | + | '''Teaching and Learning Across Significant Difference''' – Participate collaboratively and effectively in our diverse society. Communicate clearly and effectively. |

| − | Collaboration - Participate collaboratively and effectively in our diverse society. Communicate clearly and effectively. Articulate and assume responsibility for your own work. | + | '''Collaboration''' - Participate collaboratively and effectively in our diverse society. Communicate clearly and effectively. Articulate and assume responsibility for your own work. |

| − | Linking Theory and Practice - Apply qualitative, quantitative, and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines. Demonstrate integrative, independent, critical thinking. Demonstrate depth, breadth, and synthesis of learning and the ability to reflect on the personal and social significance of that learning. | + | '''Linking Theory and Practice''' - Apply qualitative, quantitative, and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines. Demonstrate integrative, independent, critical thinking. Demonstrate depth, breadth, and synthesis of learning and the ability to reflect on the personal and social significance of that learning. |

| − | Interdisciplinary – Communicate creatively and effectively. Demonstrate integrative, independent and critical thinking. Apply qualitative, quantitative, and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines. | + | '''Interdisciplinary''' – Communicate creatively and effectively. Demonstrate integrative, independent and critical thinking. Apply qualitative, quantitative, and creative modes of inquiry appropriately to practical and theoretical problems across disciplines. |

=====Reflexive Thinking===== | =====Reflexive Thinking===== | ||

| − | As a part of the work on reaccreditation this year, the college invited Elizabeth Minnich to talk with the deans and a small group of faculty working on the self-study. Her discussion of reflexive thinking captured a good deal of what Evergreen sees as distinctive and important about the education and experience that Evergreen students engage as they work in and around the curriculum as it is structured by the five foci and the six expectations. (Elizabeth K. Minnich, Knowledge, Thinking, Judgment: For Good or For Ill,” Long Island University: TASA Award Lecture, April 27, 2006; Elizabeth K. Minnich, Teaching and Thinking: Moral and Political Considerations,” Change, September/October 2003, pp.19-24) | + | As a part of the work on reaccreditation this year, the college invited Elizabeth Minnich to talk with the deans and a small group of faculty working on the self-study. Her discussion of reflexive thinking captured a good deal of what Evergreen sees as distinctive and important about the education and experience that Evergreen students engage as they work in and around the curriculum as it is structured by the five foci and the six expectations. (Elizabeth K. Minnich, "Knowledge, Thinking, Judgment: For Good or For Ill,” Long Island University: TASA Award Lecture, April 27, 2006; Elizabeth K. Minnich, Teaching and Thinking: Moral and Political Considerations,” ''Change'', September/October 2003, pp.19-24) |

| − | + | ||

Reflexive thinking begins with a question, an interrogation of the world, and an encounter with the other. As such, it involves the student in the whole process of substantive learning about subjects, disciplines and methods that is the standard domain of learning. But reflexivity is the capacity that a learner has to think about the situation and conditions that underlie her own personal and collective experience of thinking and knowing. She can be aware of how she has learned and what she has become through the process of learning. Minnich, following Nietzsche, argues this form of thinking makes the learner a “problem” for herself. Not only does the learner come to know the ostensible subject of the learning (a text, a geological strata, or a piece of music), but through that knowing new questions emerge such as: how the subject is involved in a whole array of questions about the learner’s own motives; his embeddedness in society; or his desires and development. Beyond that, reflexive thinking allows the student to ask questions about how the ostensible subject has come into being in a society and become enmeshed in a complex historical and social web of connections and power that underlie that discipline. Students learn to see the accounts of disciplines as partial. Thinking that makes our understanding of self and society problematic creates inquiry that is unbound by disciplinary concerns. As a person strives to understand his situation, an extraordinary range of understanding from the very personal to that of any array of disciplines can become critical lenses for seeing or understanding the situation. The student emerges as problems for herself that can be seen as arising from multiple points of view. | Reflexive thinking begins with a question, an interrogation of the world, and an encounter with the other. As such, it involves the student in the whole process of substantive learning about subjects, disciplines and methods that is the standard domain of learning. But reflexivity is the capacity that a learner has to think about the situation and conditions that underlie her own personal and collective experience of thinking and knowing. She can be aware of how she has learned and what she has become through the process of learning. Minnich, following Nietzsche, argues this form of thinking makes the learner a “problem” for herself. Not only does the learner come to know the ostensible subject of the learning (a text, a geological strata, or a piece of music), but through that knowing new questions emerge such as: how the subject is involved in a whole array of questions about the learner’s own motives; his embeddedness in society; or his desires and development. Beyond that, reflexive thinking allows the student to ask questions about how the ostensible subject has come into being in a society and become enmeshed in a complex historical and social web of connections and power that underlie that discipline. Students learn to see the accounts of disciplines as partial. Thinking that makes our understanding of self and society problematic creates inquiry that is unbound by disciplinary concerns. As a person strives to understand his situation, an extraordinary range of understanding from the very personal to that of any array of disciplines can become critical lenses for seeing or understanding the situation. The student emerges as problems for herself that can be seen as arising from multiple points of view. | ||

| − | As learners come to understand themselves and learning in this complex way, they exercise freedom and judgment about what they have learned about themselves, and the material, social conditions that allow this way of knowing to exist. In other words the learner starts to exercise freedom and responsibility about the knowledge he has about the society, himself. Through judgment he creates new meanings. These meanings typically do not take the given assumptions that lie behind the disciplines as settled truths; they inherently challenge established understandings. This process of creating new meanings necessarily engages the learner with others in a public process of sharing understandings. Participating in this world of reflexivity pushes the individual learner to recognize difference and diversity of views and positions. In particular it demands that the learner engage not simply in reflection, but in representational thinking, thinking through the eyes of others. This extraordinarily difficult and never completely successful mode of thinking forces a learner to take seriously the understandings and ways of perceiving and knowing that exist in the world. This process of thinking through the eyes of others demands that the learner, and indeed the community she is a part of, must learn to think historically. This means that she sees how the structure of ideas that define our views of others has come into being and is changed over time. It also implies that she sees how social institutions have grown up historically to define the place of others and ourselves in a society. Finally, knowing of this sort is iterative, each encounter, each attempt at restatement, each expanded understanding or more clearly defined insight, opens the door to response and further learning. The fun never stops. Thus reflexive and representational thinking are ultimately necessarily both very personal and public. | + | As learners come to understand themselves and learning in this complex way, they exercise freedom and judgment about what they have learned about themselves, and the material, social conditions that allow this way of knowing to exist. In other words, the learner starts to exercise freedom and responsibility about the knowledge he has about the society, himself. Through judgment he creates new meanings. These meanings typically do not take the given assumptions that lie behind the disciplines as settled truths; they inherently challenge established understandings. This process of creating new meanings necessarily engages the learner with others in a public process of sharing understandings. Participating in this world of reflexivity pushes the individual learner to recognize difference and diversity of views and positions. In particular it demands that the learner engage not simply in reflection, but in representational thinking, thinking through the eyes of others. This extraordinarily difficult and never completely successful mode of thinking forces a learner to take seriously the understandings and ways of perceiving and knowing that exist in the world. This process of thinking through the eyes of others demands that the learner, and indeed the community she is a part of, must learn to think historically. This means that she sees how the structure of ideas that define our views of others has come into being and is changed over time. It also implies that she sees how social institutions have grown up historically to define the place of others and ourselves in a society. Finally, knowing of this sort is iterative, each encounter, each attempt at restatement, each expanded understanding or more clearly defined insight, opens the door to response and further learning. The fun never stops. Thus reflexive and representational thinking are ultimately necessarily both very personal and public. |

This way of thinking about an Evergreen education is attractive because the questions that underlie it are so simple to pose and so powerful when fully examined. “How do you know what you know?” and “So what?” are the fundamental questions. These questions open up for the student the whole range of conditions that make up her position in the world and ask her to take responsibility for understanding some of the consequences of her situation and her knowledge. Evergreen programs make a wide range of choices about how much they engage in these questions, but nearly all pose them for students and urge students to take on these issues as they think about their work and evaluate their experience. | This way of thinking about an Evergreen education is attractive because the questions that underlie it are so simple to pose and so powerful when fully examined. “How do you know what you know?” and “So what?” are the fundamental questions. These questions open up for the student the whole range of conditions that make up her position in the world and ask her to take responsibility for understanding some of the consequences of her situation and her knowledge. Evergreen programs make a wide range of choices about how much they engage in these questions, but nearly all pose them for students and urge students to take on these issues as they think about their work and evaluate their experience. | ||

| − | ==== | + | ====2.A.3 Degree Programs Offered==== |

''Degree and certificate programs demonstrate a coherent design; are characterized by appropriate breadth, depth, sequencing of courses, synthesis of learning, and the assessment of learning outcomes; and require the use of library and other information sources.'' | ''Degree and certificate programs demonstrate a coherent design; are characterized by appropriate breadth, depth, sequencing of courses, synthesis of learning, and the assessment of learning outcomes; and require the use of library and other information sources.'' | ||

| + | At the time of this writing, Evergreen offers three graduate degrees, Master in Teaching (MIT), Master in Public Administration (MPA), and Master in Environmental Studies (MES). A fourth master's program, the Master of Education in Curriculum and Instruction with endorsements in Mathematics and English as a Second Language (M.Ed.), is scheduled to begin enrolling students in the summer of 2008. All three of the established master's programs have regular structures and well-established requirements that organize their work and the award of degrees. See Standard 2.D., 2.E. and 2.F. | ||

| − | + | The college offers two degree programs at the undergraduate level – the bachelor of arts degree and the bachelor of science degree. The bachelor of arts degree requires the successful completion of 180 quarter-hours of college level work. The bachelor of science degree requires 180 quarter-hours of work, including credits in mathematics, natural science, or computer science, of which 48 of which must be upper division science credit. The college has worked to identify upper division science work and faculty who have appropriate credentials to award such credit over the past several years. A combined bachelor of arts/bachelor of science degree requires at least 225 quarter-hours credit, 90 of which must be earned at Evergreen (see [http://www.evergreen.edu/catalog/2008-09/ http://www.evergreen.edu/catalog/2008-09/]). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | The college offers two degree programs at the undergraduate level | + | |

| − | ====2.A.4 | + | ====2.A.4 Degree Requirements==== |

''The institution uses degree designators consistent with program content. In each field of study or technical program, degree objectives are clearly defined: the content to be covered, the intellectual skills, the creative capabilities, and the methods of inquiry to be acquired; and, if applicable, the specific career-preparation competencies to be mastered.'' | ''The institution uses degree designators consistent with program content. In each field of study or technical program, degree objectives are clearly defined: the content to be covered, the intellectual skills, the creative capabilities, and the methods of inquiry to be acquired; and, if applicable, the specific career-preparation competencies to be mastered.'' | ||

The institution offers two undergraduate degrees, the bachelor of arts and the bachelor of science as described above. Each degree program requires 180 quarter-hours of credit. As shown above, the Six Expectations ask students to develop a focus for their work using the college’s offerings and independent work developed with faculty to complete their program of study. The bachelor of science requires a minimum of 72 quarter-hours in natural science, mathematics, or computer science, including at least 48 upper division quarter-hours awarded by faculty in the sciences. Each master's program has program-specific outcomes for the degrees offered as described in sub-section 2.D. | The institution offers two undergraduate degrees, the bachelor of arts and the bachelor of science as described above. Each degree program requires 180 quarter-hours of credit. As shown above, the Six Expectations ask students to develop a focus for their work using the college’s offerings and independent work developed with faculty to complete their program of study. The bachelor of science requires a minimum of 72 quarter-hours in natural science, mathematics, or computer science, including at least 48 upper division quarter-hours awarded by faculty in the sciences. Each master's program has program-specific outcomes for the degrees offered as described in sub-section 2.D. | ||

| − | ====2.A.5 | + | ====2.A.5 Intensive programs==== |

''The institution provides evidence that students enrolled in programs offered in concentrated or abbreviated timeframes demonstrate mastery of program goals and course objectives.'' | ''The institution provides evidence that students enrolled in programs offered in concentrated or abbreviated timeframes demonstrate mastery of program goals and course objectives.'' | ||

Over the past ten years, Evergreen has moved to offer weekend intensive programs at both the graduate and undergraduate level. This schedule has increased the accessibility of our programs to place-bound students. Programs offered on either the regular or intensive schedule expect approximately 30 hours of study and class attendance for each unit of credit earned. | Over the past ten years, Evergreen has moved to offer weekend intensive programs at both the graduate and undergraduate level. This schedule has increased the accessibility of our programs to place-bound students. Programs offered on either the regular or intensive schedule expect approximately 30 hours of study and class attendance for each unit of credit earned. | ||

| − | ====2.A.6 | + | ====2.A.6 Program Tuition==== |

''The institution is able to equate its learning experiences with semester or quarter credit hours using practices common to institutions of higher education, to justify the lengths of its programs in comparison to similar programs found in regionally accredited institutions of higher education, and to justify any program-specific tuition in terms of program costs, program length, and program objectives.'' | ''The institution is able to equate its learning experiences with semester or quarter credit hours using practices common to institutions of higher education, to justify the lengths of its programs in comparison to similar programs found in regionally accredited institutions of higher education, and to justify any program-specific tuition in terms of program costs, program length, and program objectives.'' | ||

Evergreen expects contact hours with students and the quarter-long length of its programs to be similar to those expected at other Washington public universities. Evergreen tuition is based on level (bachelor's or master's), residency, and the number of credits. There is no special program-specific tuition. | Evergreen expects contact hours with students and the quarter-long length of its programs to be similar to those expected at other Washington public universities. Evergreen tuition is based on level (bachelor's or master's), residency, and the number of credits. There is no special program-specific tuition. | ||

| − | ====2.A.7 | + | ====2.A.7 Curriculum Planning==== |

''Responsibility for design, approval, and implementation of the curriculum is vested in designated institutional bodies with clearly established channels of communication and control. The faculty has a major role and responsibility in the design, integrity, and implementation of the curriculum.'' | ''Responsibility for design, approval, and implementation of the curriculum is vested in designated institutional bodies with clearly established channels of communication and control. The faculty has a major role and responsibility in the design, integrity, and implementation of the curriculum.'' | ||

| − | |||

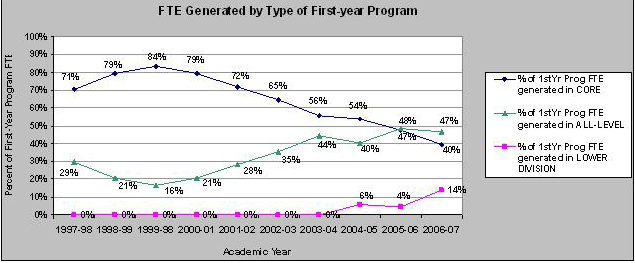

The curriculum at Evergreen is planned by the faculty, the academic deans, and the directors of off-site programs. The undergraduate curriculum at Evergreen is a complex mixture of regularly repeating offerings, irregularly repeating offerings, and one-time efforts. The curriculum is revised annually. Each planning unit (see glossary) is responsible for defining and staffing its offerings and is expected to contribute 20% of its faculty time to Core (first-year) programs and another 20% to inter-area (teams involving faculty from two or more planning units) work. Planning in any given year is designed to develop a catalog for two years hence. Thus in the 2008-09 school year, faculty will be designing the curriculum for the 2010-11 school year. The curriculum dean(s) in collaboration with the Planning Unit Coordinators (PUCs) organize a series of all-faculty meetings in early fall quarter that are designed to solicit ideas, proposals, and suggestions for inter-area work at the first year and above level. | The curriculum at Evergreen is planned by the faculty, the academic deans, and the directors of off-site programs. The undergraduate curriculum at Evergreen is a complex mixture of regularly repeating offerings, irregularly repeating offerings, and one-time efforts. The curriculum is revised annually. Each planning unit (see glossary) is responsible for defining and staffing its offerings and is expected to contribute 20% of its faculty time to Core (first-year) programs and another 20% to inter-area (teams involving faculty from two or more planning units) work. Planning in any given year is designed to develop a catalog for two years hence. Thus in the 2008-09 school year, faculty will be designing the curriculum for the 2010-11 school year. The curriculum dean(s) in collaboration with the Planning Unit Coordinators (PUCs) organize a series of all-faculty meetings in early fall quarter that are designed to solicit ideas, proposals, and suggestions for inter-area work at the first year and above level. | ||

| Line 166: | Line 162: | ||

Usually planning units meet at the fall faculty retreat and in the latter half of the quarter to identify their ongoing staffing needs and identify planning unit members interested in working in inter-area and Core. These meetings involve looking at the curriculum of the unit over a four-year period: the year being planned, the current year, the next year, and usually considering the year following the year being planned for. This iterative retrospective-prospective overview helps identify the needs for prerequisites; identify the appropriate cycle year for regularly, but not annually, repeating programs; identify questions of balance in subject matter; and clarify individual contributions to the units’ work. Most of the ongoing repeated work and advanced disciplinary work at the college is organized by planning units. | Usually planning units meet at the fall faculty retreat and in the latter half of the quarter to identify their ongoing staffing needs and identify planning unit members interested in working in inter-area and Core. These meetings involve looking at the curriculum of the unit over a four-year period: the year being planned, the current year, the next year, and usually considering the year following the year being planned for. This iterative retrospective-prospective overview helps identify the needs for prerequisites; identify the appropriate cycle year for regularly, but not annually, repeating programs; identify questions of balance in subject matter; and clarify individual contributions to the units’ work. Most of the ongoing repeated work and advanced disciplinary work at the college is organized by planning units. | ||

| − | Core and inter-divisional planning, which began early in the fall with the meeting to share ideas, continues more or less informally as faculty follow up ideas with each other and attend meetings called by either the Core dean or the curriculum dean to firm up and identify programs. In addition to the intricate matchmaking that occurs within program teams, the PUCs and curriculum deans are involved in a complex process of informal negotiation and planning to ensure the appropriate number of first-year seats (those in Core and then those seats identified for freshmen in all-level or lower-division programs) and appropriate coverage of planning unit repeated offerings. All of these decisions are made in negotiations among faculty and deans and are vetted to the planning unit meetings in winter quarter so that faculty can evaluate and respond to the area’s curriculum and its relation to other Core and inter-area offerings. This complex two-tracked process within and between the planning units culminates in a draft curriculum by the end of winter quarter. The final negotiations between planning units and the deans, the creation of catalog copy for programs, and the identification of staffing needs is carried out by PUCs who are given release time spring quarter to complete these duties. One important byproduct of the curriculum planning process is the awareness of areas of demand in the curriculum and | + | Core and inter-divisional planning, which began early in the fall with the meeting to share ideas, continues more or less informally as faculty follow up ideas with each other and attend meetings called by either the Core dean or the curriculum dean to firm up and identify programs. In addition to the intricate matchmaking that occurs within program teams, the PUCs and curriculum deans are involved in a complex process of informal negotiation and planning to ensure the appropriate number of first-year seats (those in Core and then those seats identified for freshmen in all-level or lower-division programs) and appropriate coverage of planning unit repeated offerings. All of these decisions are made in negotiations among faculty and deans and are vetted to the planning unit meetings in winter quarter so that faculty can evaluate and respond to the area’s curriculum and its relation to other Core and inter-area offerings. This complex two-tracked process within and between the planning units culminates in a draft curriculum by the end of winter quarter. The final negotiations between planning units and the deans, the creation of catalog copy for programs, and the identification of staffing needs is carried out by PUCs who are given release time spring quarter to complete these duties. One important byproduct of the curriculum planning process is the awareness of areas of demand in the curriculum and supplementary short-term and long-term hiring needs. |

Unlike the full-time curriculum, the Evening and Weekend Studies (EWS) curriculum is planned on a one-year cycle. This structure allows the curriculum to adapt more quickly to shifts in the student body and is an aspect of the service orientation of the EWS area. The EWS dean and the continuing faculty in the area jointly control planning for the area. | Unlike the full-time curriculum, the Evening and Weekend Studies (EWS) curriculum is planned on a one-year cycle. This structure allows the curriculum to adapt more quickly to shifts in the student body and is an aspect of the service orientation of the EWS area. The EWS dean and the continuing faculty in the area jointly control planning for the area. | ||

| Line 172: | Line 168: | ||

Planning in the graduate programs is controlled by their respective faculty and is described in 2.D. | Planning in the graduate programs is controlled by their respective faculty and is described in 2.D. | ||

| − | ====2.A.8 | + | ====2.A.8 Library and Information Resources==== |

''Faculty, in partnership with library and information resources personnel, ensure that the use of library and information resources is integrated into the learning process.'' | ''Faculty, in partnership with library and information resources personnel, ensure that the use of library and information resources is integrated into the learning process.'' | ||

The tension between the demands of discipline-based curriculum where programs are created to meet known (or presumed) needs with known prerequisites and outcomes on the one hand, and the demands of freely chosen inquiry based on broad skills of knowing, reasoning, and communicating about issues whose outcome remain to be discovered through experience on the other, is the context within which the curriculum comes into being at Evergreen. The college puts a premium on student research work in both independent learning contracts, and group and individual research projects within programs. Library and information services at Evergreen have from the very beginning had to adapt themselves to the complex ever changing focus of the programs and faculty. This has meant that these services have had to be very broad and carefully coordinated with emerging curricular needs. Standard 5.B.2. details the complex intersection of library and information resource instruction at the college. | The tension between the demands of discipline-based curriculum where programs are created to meet known (or presumed) needs with known prerequisites and outcomes on the one hand, and the demands of freely chosen inquiry based on broad skills of knowing, reasoning, and communicating about issues whose outcome remain to be discovered through experience on the other, is the context within which the curriculum comes into being at Evergreen. The college puts a premium on student research work in both independent learning contracts, and group and individual research projects within programs. Library and information services at Evergreen have from the very beginning had to adapt themselves to the complex ever changing focus of the programs and faculty. This has meant that these services have had to be very broad and carefully coordinated with emerging curricular needs. Standard 5.B.2. details the complex intersection of library and information resource instruction at the college. | ||

| − | ====2.A.9 | + | ====2.A.9 Structural Elements of the Evergreen Curriculum==== |

''The institution’s curriculum (programs and courses) is planned both for optimal learning and accessible scheduling.'' | ''The institution’s curriculum (programs and courses) is planned both for optimal learning and accessible scheduling.'' | ||

| Line 195: | Line 191: | ||

Most student work at Evergreen is carried out in one form or another of full-time study. The pedagogical rationale here arises out of the coordinated study programs, especially those with a thematic base. These complex, multi-stranded, highly integrated programs make little or no sense when significant elements are removed. Similar intensive full-time work is often expected in single faculty full-time programs. This feature of the college provides the intellectual intensity described above, but also provides the flexibility of scheduling that allows the college to offer genuinely innovative work in a number of fields where large blocks of time and travel are required. Beyond this, the reality that most faculty, in most programs, have control of most of their students’ time in class, and meet with those students generally fourteen to twenty hours per week, means that they know their students' needs, capacities, and desires well. This knowledge allows for strong guidance and modification of program tasks, allows complex reflective evaluations of students, and lays the groundwork for effective advising. The college has allowed significantly more part-time work in recent years in Evening and Weekend Studies. The part-time study is structured both through half-time coordinated studies and course work. | Most student work at Evergreen is carried out in one form or another of full-time study. The pedagogical rationale here arises out of the coordinated study programs, especially those with a thematic base. These complex, multi-stranded, highly integrated programs make little or no sense when significant elements are removed. Similar intensive full-time work is often expected in single faculty full-time programs. This feature of the college provides the intellectual intensity described above, but also provides the flexibility of scheduling that allows the college to offer genuinely innovative work in a number of fields where large blocks of time and travel are required. Beyond this, the reality that most faculty, in most programs, have control of most of their students’ time in class, and meet with those students generally fourteen to twenty hours per week, means that they know their students' needs, capacities, and desires well. This knowledge allows for strong guidance and modification of program tasks, allows complex reflective evaluations of students, and lays the groundwork for effective advising. The college has allowed significantly more part-time work in recent years in Evening and Weekend Studies. The part-time study is structured both through half-time coordinated studies and course work. | ||

| − | |||

=====Student Self-Directed Study===== | =====Student Self-Directed Study===== | ||

| Line 217: | Line 212: | ||

Three major initiatives in the past ten years have considered transcript evaluations. All of these start from the premise that a complete and well written transcript is an asset to students as they proceed from Evergreen and from a resistance to the idea of reducing evaluation to grades or rating forms. They reflect the need to create more concise and well-voiced evaluations in a timely and coherent manner. Two major committees, the first in 1996-1997 and the second in 2003-2004, produced a set of arguments for the continuing utility of the evaluation process and support for the idea that there was no single universal process for evaluation. The latter DTF developed an important document on faculty narrative strategies and provided guidelines on the length and nature of the evaluation process. A second study group (Evaluation Processing) in 2002-2004 focused on procedures for the reorganization of the handling of evaluations and their storage and maintenance as electronic documents. This process has sped the production of transcript evaluations. The formal faculty evaluation documents contain a program description identifying the work of the program, a formal assessment of the student’s work, and the identification of the program’s activities as subject equivalencies. | Three major initiatives in the past ten years have considered transcript evaluations. All of these start from the premise that a complete and well written transcript is an asset to students as they proceed from Evergreen and from a resistance to the idea of reducing evaluation to grades or rating forms. They reflect the need to create more concise and well-voiced evaluations in a timely and coherent manner. Two major committees, the first in 1996-1997 and the second in 2003-2004, produced a set of arguments for the continuing utility of the evaluation process and support for the idea that there was no single universal process for evaluation. The latter DTF developed an important document on faculty narrative strategies and provided guidelines on the length and nature of the evaluation process. A second study group (Evaluation Processing) in 2002-2004 focused on procedures for the reorganization of the handling of evaluations and their storage and maintenance as electronic documents. This process has sped the production of transcript evaluations. The formal faculty evaluation documents contain a program description identifying the work of the program, a formal assessment of the student’s work, and the identification of the program’s activities as subject equivalencies. | ||

| − | ====2.A.10 | + | ====2.A.10 Prior Learning from Experience==== |

''Credit for prior experiential learning is awarded only in accordance with Policy 2.3 Credit for Prior Experiential Learning'' | ''Credit for prior experiential learning is awarded only in accordance with Policy 2.3 Credit for Prior Experiential Learning'' | ||

| Line 228: | Line 223: | ||

Evergreen awards up to a maximum of forty-five PLE credits, but sixteen of those forty-five are earned in PLE document writing. They can be awarded additional credit above sixteen to achieve the full forty-five, but most are awarded less than that. Credit awards are based on documentation and students are not assured of receiving the credit that they may request at any time in this process. Credit is identified as PLE via the narrative evaluation of the student's work. | Evergreen awards up to a maximum of forty-five PLE credits, but sixteen of those forty-five are earned in PLE document writing. They can be awarded additional credit above sixteen to achieve the full forty-five, but most are awarded less than that. Credit awards are based on documentation and students are not assured of receiving the credit that they may request at any time in this process. Credit is identified as PLE via the narrative evaluation of the student's work. | ||

| − | The Prior Learning adjunct faculty ensures that requested credit does not duplicate credit already on the student's transcript. After the faculty team awards credit, the student receives a formal evaluation, is billed for the credit awarded, and the credit is entered on his transcript | + | The Prior Learning adjunct faculty ensures that requested credit does not duplicate credit already on the student's transcript. After the faculty team awards credit, the student receives a formal evaluation, is billed for the credit awarded, and the credit is entered on his transcript (see [[Media: ple_infopage.pdf|PLE Homepage]]). |

| − | ==== | + | ====2.A.11/12 Program additions or deletions==== |

''Policies, regulations, and procedures for additions and deletions of courses or programs are systematically and periodically reviewed.'' | ''Policies, regulations, and procedures for additions and deletions of courses or programs are systematically and periodically reviewed.'' | ||

| Line 236: | Line 231: | ||

and has not deleted any programs. The new programs include: | and has not deleted any programs. The new programs include: | ||

| − | * | + | *A new concentration track in Tribal Governance and Administration within the existing Master of Public Administration (MPA) program. |

| − | * | + | *The Extended Education program. |

| − | * | + | *A new pathway for students seeking to earn a dual Master of Public Administration and Master of Environmental Studies degree. |

| − | * | + | *One additional site for the Tribal Reservation-based/Community-determined Program (RBCD). |

| − | * | + | *The Master of Education (M.Ed.) program. |

| − | New academic programs are vetted through the deans, planning unit coordinators, Faculty Agenda Committee, and ultimately the faculty. If approved, the | + | New academic programs are vetted through the deans, planning unit coordinators, Faculty Agenda Committee, and ultimately the faculty. If approved, the provost requests board of trustee approval. |